Have the Difficult Conversation

As an FFT Fellow, I reached out to ask if I could share a post with all of you.

The first generation of my Ukrainian family born in the United States, my heart aches as Russia’s invasion unfolds. Mine is an activist family – we fought for human rights in Ukraine, raised funds for humanitarian aid after the 1986 nuclear explosion of Chornobyl (Ukrainian spelling), and raised awareness about our rich history and culture through many organizations including my years as an officer of the Ukrainian Student Association at the State University of New York at Buffalo. It’s only in recent years that I’ve made the connection that it was very likely these formative years that paved the way for me becoming an educator — which forces me daily to reflect, stretch and grow, not only as a teacher but also a learner.

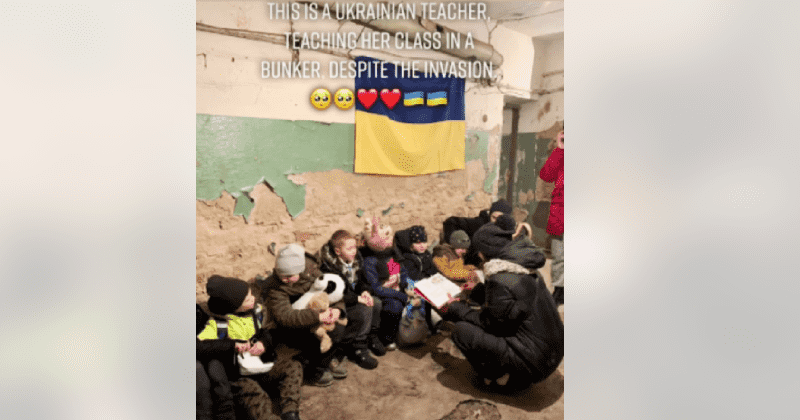

I am sure many of you saw the above photo, originally posted on TikTok, that went viral a couple weeks ago of a Ukrainian teacher with her students huddled up against the wall of a bomb shelter as she continued on with her instruction trying to offer them some normalcy. I haven’t been able to let go of this image and made a commitment to myself to continue my work in honor of this courageous teacher.

As an educator committed to both personal and professional growth, I have come to strongly believe…

it’s my responsibility and that of educators around the world to have difficult conversations with our students – not just about this moment in time with the war in Ukraine but anytime important issues arise from human rights violations, racial injustices, ongoing conflicts, etc.

We cannot underestimate the intellect, curiosity, empathy, and capacity of children, even our youngest. There are some that would argue that it’s too scary or inappropriate to discuss certain heavy topics/issues with specific stages of development. I say no, it’s never too young to begin having discussions about important issues. As educators and parents, we need to be sensitive and mindful of the language we use and how we frame discussions but even the youngest have a lot to say about what they believe peace is, how it feels, what it looks like, etc. Let me tell you – they have plenty to share. Not only is seeing war emerge hard enough, it is likely that all of us, from our youngest learners to ourselves, have questions that we might not have answers. Together, we can create a safe place to explore and navigate these challenging and uncomfortable realities.

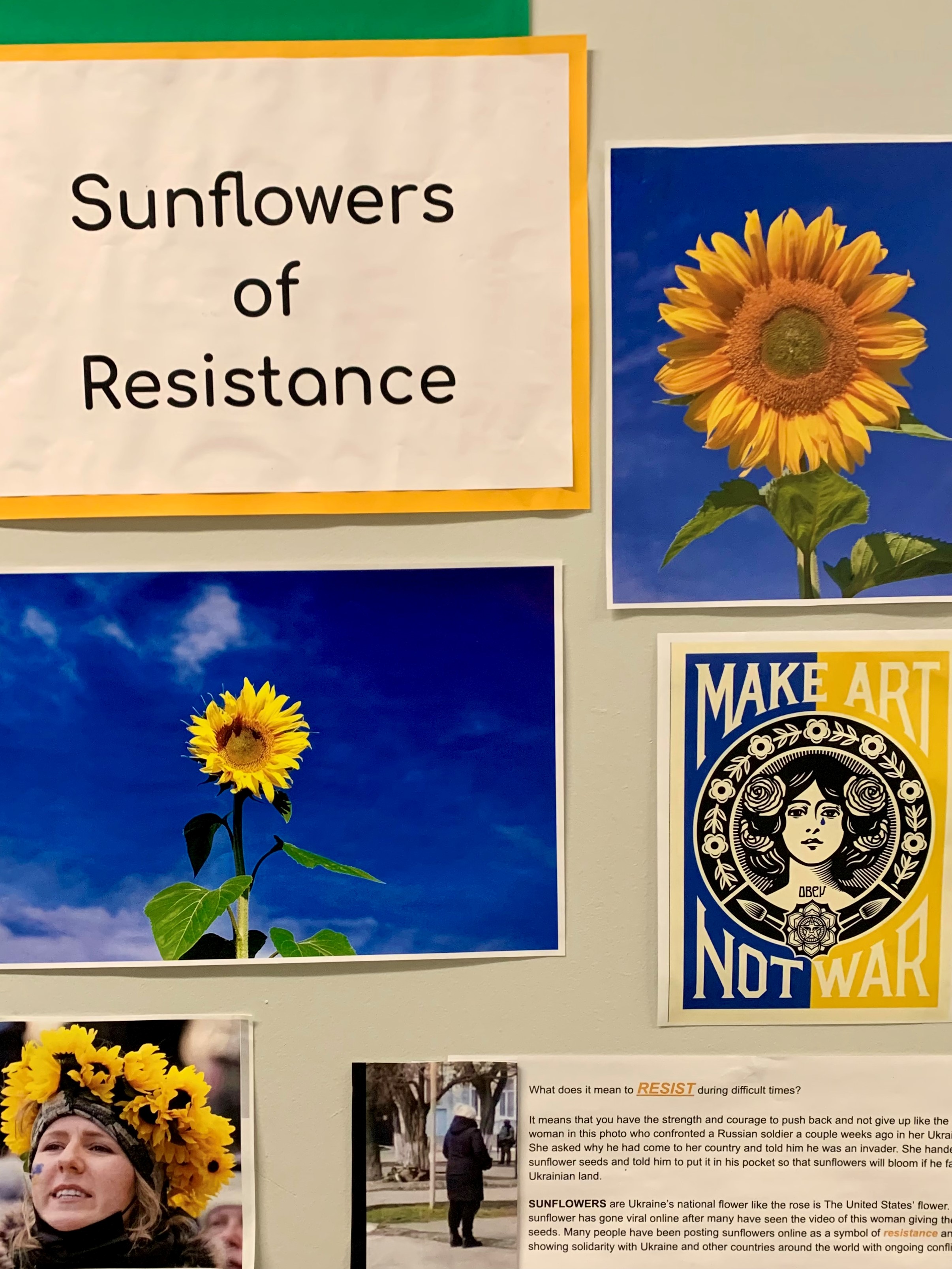

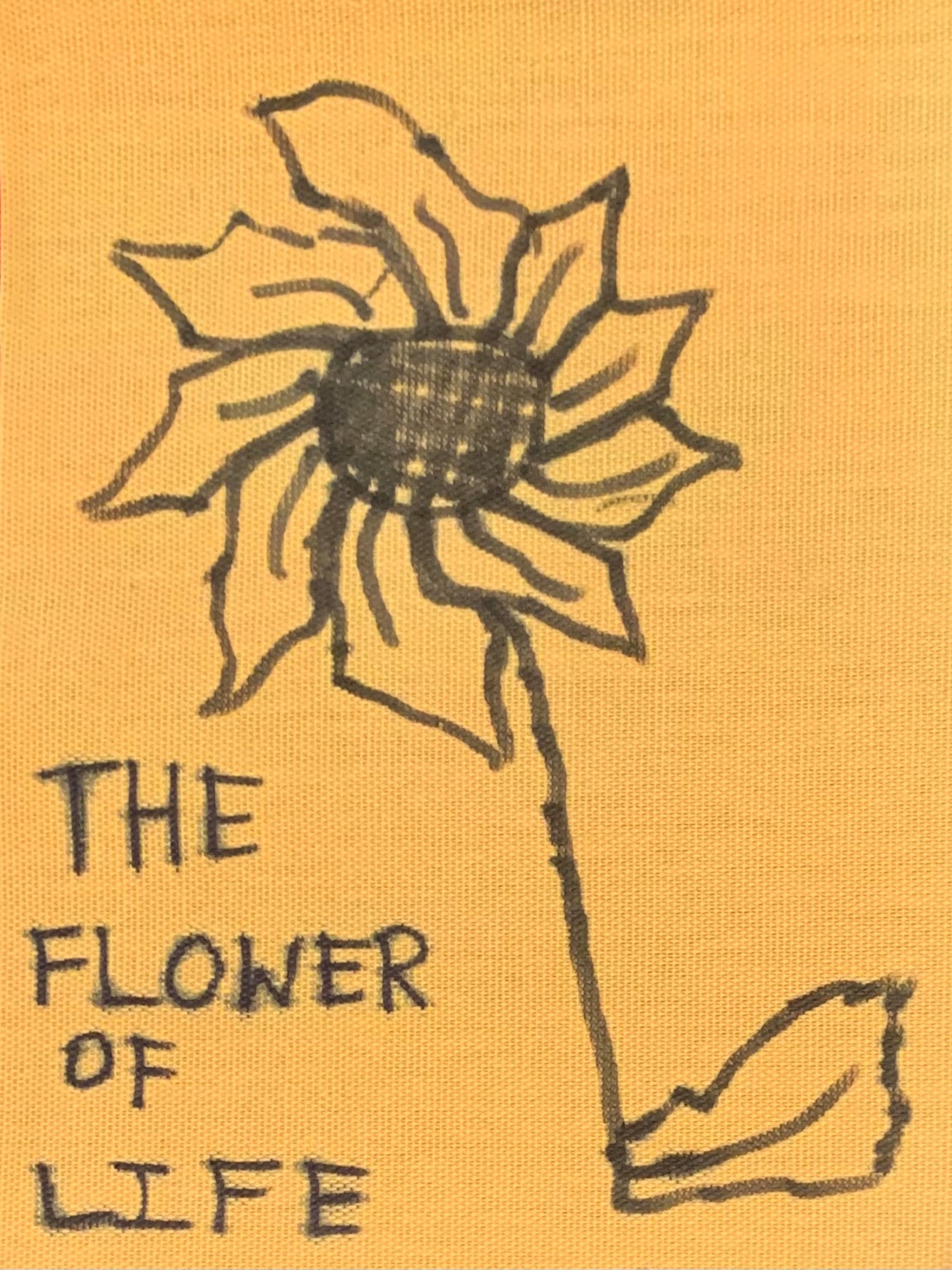

Over the past few weeks, my grade 1-3 classes have had these discussions in art class, most often initiated by them, that led to a couple initiatives at my school. One is a project I’ve titled Sunflowers of Resistance after learning that not only is the sunflower Ukraine’s national flower, but in recent weeks became a symbol of resilience and resistance. All of our students, grades 1 -8, currently in visual arts created one.

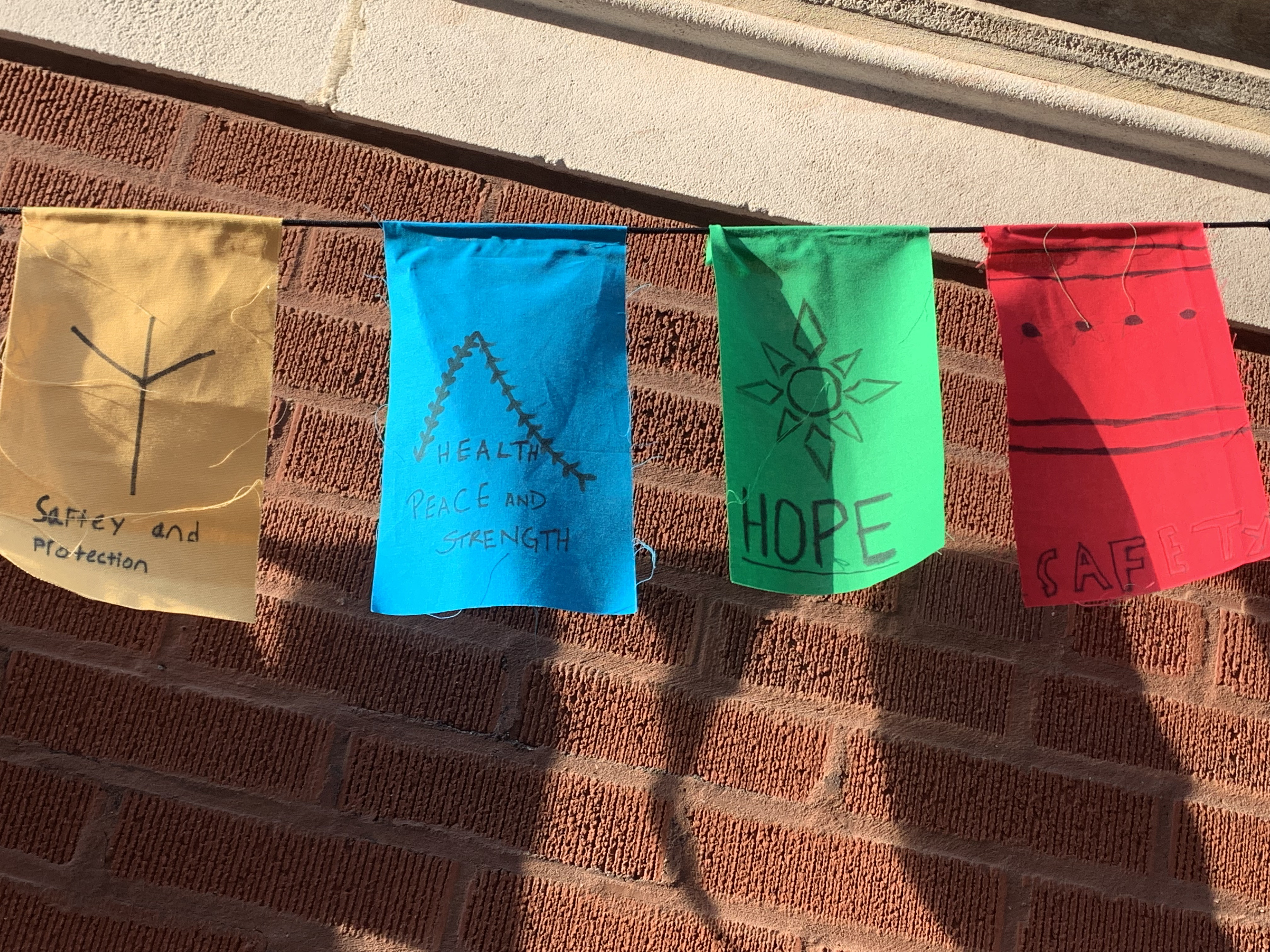

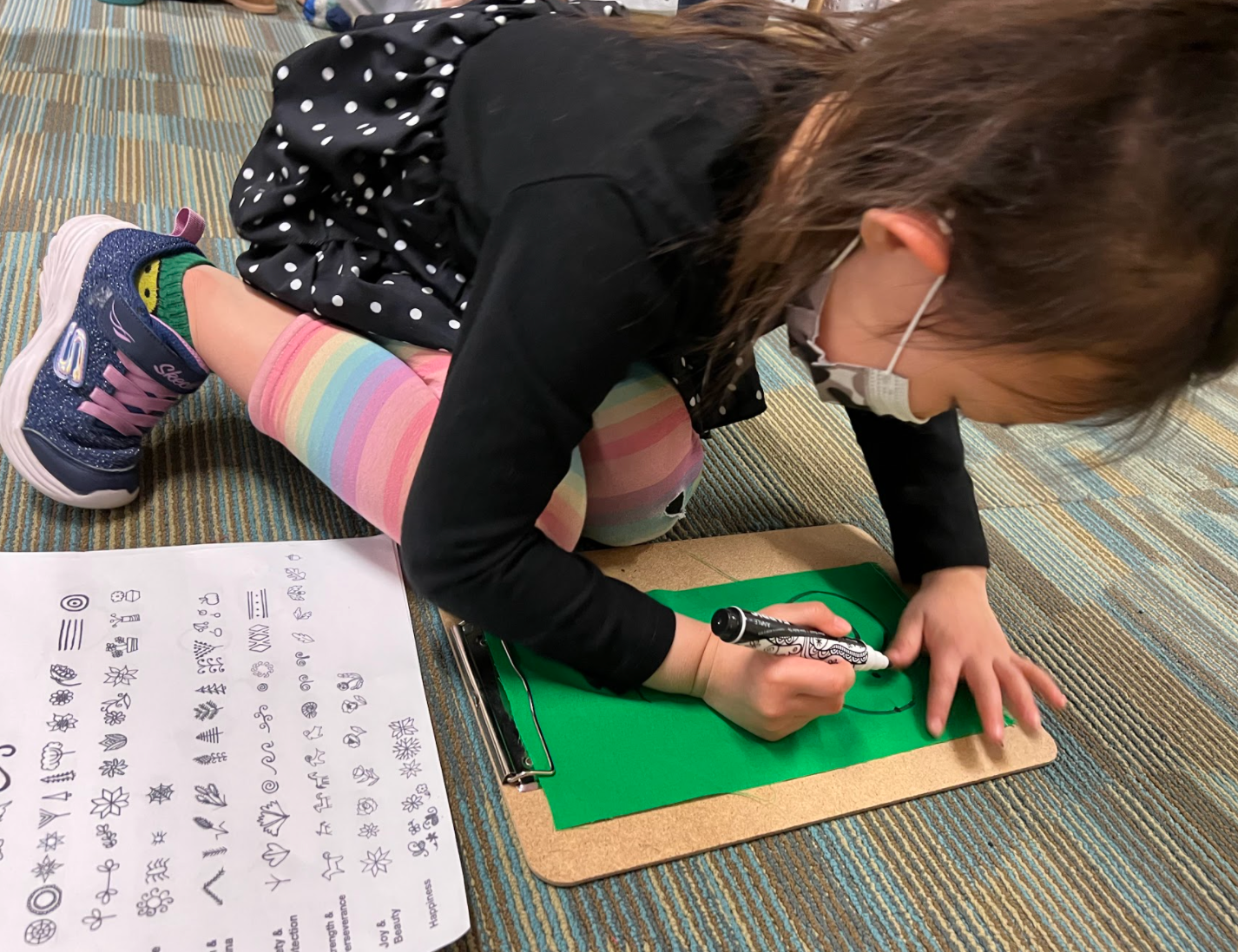

To bring our community together and encourage dialogue and awareness, I also spearheaded a community-wide PEACE Project. Over the past week, every student (Pre-K-8), staff, faculty and parents were invited to create a peace flag by selecting a Ukrainian pysanky (Easter egg) symbol of hope, love, strength, protection, health, perseverance or change to draw on their flag along with a wish and/or prayer for peace. The peace flags have been strung on rope and hung on both the interior and exterior of our school building.

Here is the statement that accompanies our PEACE project:

Our school recognizes that atrocities towards any one individual or peoples are in violation of their rights to live freely and safely. In light of the recent events and war in Ukraine, as well as ongoing conflict which harms and displaces many people around the world, including right here in Chicago, we stand in solidarity for peace and unity.

To give illustration to our collective hopes for and actions toward peaceful resolutions, we raise these flags in the spirit of reflection, in support of these crises ending swiftly, and as a reminder that we are united by our shared humanity.

These five colors are most commonly represented in every nation’s flag. Community members were invited to draw a symbol that speaks most to what is in their heart. The symbols derive from the ancient Ukrainian art form of pysanky, decorated eggs. A text with either the meaning of the symbol and/or a wish, intention, or prayer accompanies the symbol.

Fellow educators, please lean into the challenge and discomfort of navigating these topics. We expect this of our students and we need to be exemplars, ourselves, and guide them. I offer myself as a resource for anyone who wants to brainstorm, have a safe place to talk, and/or find ways to integrate art into your classroom.

Additionally, shared below are a number of resources for our own learning and processing, as well as that with students of all ages.

With Peace & Hope,

Olenka Bodnarskyj

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]Teaching Resources:

- EducationWeek, How to Talk With Students About the Russia-Ukraine War: 5 Tips

- MsGreenEdu, Sample Lesson on History of Ukraine and Russia

- The Choices Program, The Ukraine Crisis

- New York Times, Lesson of the Day: The Invasion of Ukraine: How Russia Attacked and What Happens Next

- Hanane Kai Studio, Children in our World book series

- Teaching for Change, Booklist on war and anti-war

- Colours of Us, Books about peace

- PBS Kids, Books about peace

- LiberatED Resource_Discussing Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine with Students.pdf

- An elementary teacher in Bellingham, WA created this sharable slideshow on Globalism and empathy

- Educators Institute for Human Rights, list of resources for educators

- EdWeek, 8 Resources Teachers Are Using to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

- ABCNews, Honesty, reassurance: How to talk to kids about Ukraine

- PBS News Hour, Tips for helping young people cope with news about Ukraine and Russia

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Olenka Bodnarskyj is a Lower School teacher at Chicago’s Catherine Cook School. With her 2017 FFT grant, she explored aspects of the Japanese aesthetic Wabi-sabi through experiential learning in Nara and Tokyo, Japan, to develop of a unit that sheds light on similarities and differences between eastern and western ideals of art and nature.

Olenka Bodnarskyj is a Lower School teacher at Chicago’s Catherine Cook School. With her 2017 FFT grant, she explored aspects of the Japanese aesthetic Wabi-sabi through experiential learning in Nara and Tokyo, Japan, to develop of a unit that sheds light on similarities and differences between eastern and western ideals of art and nature.

Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs