On Pearl Harbor Day, we remember the 2,403 people killed in the surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. The “date which will live in infamy” launched America’s entry into World War II; the bombings also resulted in the internment of 7,000 Japanese American citizens in relocation centers by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Teaching the complexities of this time is complex in and of itself for Tim Barry. His students at Nathan Hale Middle School in Coventry, CT, fall within a wide range of ability levels.

“This drastic range creates difficulty when choosing and providing engaging and appropriate text for students of all abilities,” explained Tim. “Fortunately, with the broad scope of our World War II unit, we are able to provide high interest and appropriately leveled options so that all students may contribute and draw connections to classroom discussion and produce work that they can be proud of.”

But that unit lacked dialogue about the domestic impact of the war. Tim designed a Fund for Teachers fellowship fill that gap and, last summer, examined life in and around Japanese Relocation Camps in Utah and Colorado to help students:

- Connect to the past and apply that knowledge to the current climate in the United States?

- Draw parallels between the treatment of Japanese Americans in the United States and Jewish (and other minority) people in Europe during WWII?

- Understand the Pyramid of Hate and how the act of dehumanization impacts individuals and large groups through self reflection and journaling, and

- Support other disciplines across the curriculum such as math (budgeting), social studies (constitutional questions), and science (geographic significance of camps and land features that made them ideal).

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”10px 0px 10px 0px”]

Last summer, I was fortunate to travel to Colorado and Utah to study Japanese Internment Camps as part of my Fund For Teachers fellowship. My intention was to supplement our current World War II unit with experiences from the home front to allow students to draw parallels in today’s climate of cultural bias. I want my students to draw inspiration my own curiosity and go out and explore the world. I want them to challenge what they know or think they know and I want them to be acutely aware of how history has a tendency to repeat itself.

Granada Relocation Center memorial

Trip Details: I spent nine days traveling from the Topaz Camp in Delta, Utah to the Moab Isolation Center in Moab, Utah and finally to Granada Relocation Center (Amache) in Granada, Colorado. In Delta, I was struck by the beautifully curated Topaz Museum which highlighted the blending of traditional Japanese culture with the easily recognizable American identity of the time. High school yearbooks, recounts of baseball games, and a letterman’s jackets sat side-by-side with instruments of the Japanese tea ceremony and watercolor paintings. Despite the dramatic civil rights violations perpetrated by the United States government, these proud people still created a sense of normalcy and everyday life. The message of their resilience is one that I hope will resonate with my students.

Pictured with Mr. Kitajima and Dr. Clark

The highlight of my trip was being able to connect with Denver University at their biennial open house at the Amache site in Colorado. There, I was introduced to Dr. Bonnie Clark who is the Project Director of the DU Amache Research Project. I was able to meet several former internees of the camp, including 87 year old, Mr. Ken Kitajima who was a resident of the camp from ages 12-15. My hope is that I can provide my students with a first hand account of what it was like to be of middle school age in a Relocation Camp. I plan to connect with Mr. Kitajima virtually to conduct interviews and provide insight into his experience. Perspective is one of the most important things I can offer to my students.

Middle school is a trying time and although the experiences of my students will be different than those of the past, the challenges will not be unique. My hope is that my journey will foster a sense of intellectual curiosity as my students create their own world view and tackle the test of growing up in an increasingly demanding world.

The digital world in which we live allows people to instantly access information and make snap decisions based on their own experiences and biases, yet we don’t often slow down to assess all sides of a story. Ultimately, I want my students to be willing to challenge what is accepted by society and greet people from all walks of life with an open mind.

The main thing that I was able to bring forth and offer to my students was perspective. In our curriculum, we dive deeply into the ideals in which the nation was built upon, the Constitution, Supreme Court cases, and World War II. Through my experiences at the Japanese Relocation Camps I can provide an alternative lens in which students can view historical events and how they correlate to our society today.

We broached difficult topics such as governmental policy, Supreme Court decision making, modern and historical biases, and comparing and contrasting Germany’s Nuremberg Laws and Executive Order 9066 of the United States. As an 8th grade student is developing their own world view, the definition of “American” can mean many different things to each individual. Many conversations had to be delicately handled as students progressed through a wide array of emotions and processed preconceived notions. I’ve seen students find their own voice to respectively challenge the biases of another. Seeing a quiet and reserved student willing to speak for those who are unable to speak for themselves is an amazing thing. However, the greatest impact is to see a student challenge their OWN beliefs and to privately approach me and identify that their world view is shifting through our discussion.

For more than a decade, Tim has empowered his students to take ownership over their education and to become independent learners while focusing on character and integrity. Throughout his teaching career, he has coached athletics at both the middle and high school levels and views the competition field as an extension of the classroom where students can push themselves.

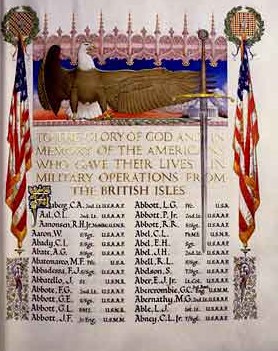

“When applying for the Fund for Teachers grant, I researched my grandfather’s military service and his path from Nebraska to Normandy,” said Dan. “On D-Day, he flew the Boeing B-17 with the USAF 94th squadron from the

“When applying for the Fund for Teachers grant, I researched my grandfather’s military service and his path from Nebraska to Normandy,” said Dan. “On D-Day, he flew the Boeing B-17 with the USAF 94th squadron from the