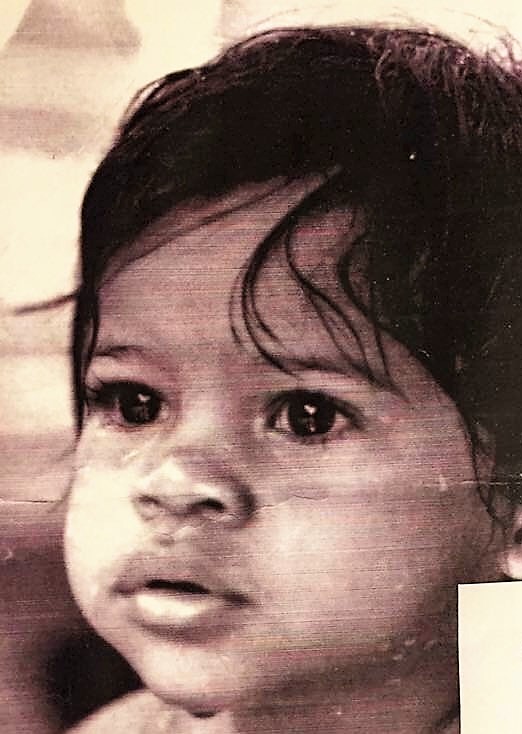

Her American name is Kim Elizabeth DeMarco. The name given by her Vietnamese mother and American father, a soldier, is Hoang Thi Thanh. Nuns who found her as an infant covered with mud and hay in a bombed village named her Marie Noel. On her Fund for Teachers fellowship, Kim returned to Vietnam with teammate Amanda Miser to research personal histories and genetic blueprints while experiencing the culture, history and schools across Vietnam to bridge the gap between students of diverse cultures and encourage a celebration of difference while enhancing discourse.

On the website created for students at Franklin H. Mayberry Elementary School in East Hartford, CT, Kim shares her harrowing adoption story.

“Sister Marie Angela brought me to the Sacred Heart Orphanage in Da Nang, which was run by an organization called Friends of Vietnam and where American doctors and French nuns took care of me. Sister Mari Angela was in constant communication with my soon to be adopted parents [in Fairfield, CT]. When the communists came up north, the orphanage had to be quickly abandoned. My soon to be adopted parents thought they had lost me, since there was no contact with the nuns for months. I was supposed to come to the United States at the age of three months old, I was now going onto the age of one and a half and still in Vietnam.

…The nuns moved me from Sacred Heart Orphanage to Kim-Long Orphanage, then to another orphanage called AM Nursery. From there I was moved again to Allambie Orphanage in Ho Chi Mingh City (Saigon). I stayed there until it was my time to depart to the states. I was one of the last planes to leave from Saigon before the war became really bad. I was escorted from Vietnam by Frank and Evelyn Zember. I first flew to France with the other orphans and then on to the United States and JFK airport.

It took a very long time to assimilate into a new country and family. I cried all of the time and did not know how to speak any English. My parents did not know what to feed me and, therefore, fed me rice and then gradually fed me American food. My adopted mom would tell me stories about how she would find food hidden in my crib, and how she would constantly try to explain to me how there always will be food for me. I would eat off of everyone else’s plates even every last morsel. Having an abundant amount of food was very rare for me. I had many fears such as starvation, sleeping in the dark and staying in a crib. When I would hear the sound of thunder I would scream and cry, which my parents believes was a reminder of the war.”

Read Kim’s entire account here.

On their fellowship Kim and Amanda visited the Allambie Orphanage where Kim lived for one year. Warmly welcomed by the orphanage’s founder, Suzanne, the teachers spent the night with the children, who left a lasting mark on Kim’s heart. They shared about the emotional day on their blog:

“Suzanne had a whole day planned for us…from lunch to dropping us at the Vietnam War Memorial to finally visiting the orphanage we’ve waited months to see with this woman who Kim has so many connections to.

Visiting the Memorial was unexpected. Suzanne strongly recommended we go here so we could understand more about the circumstances surrounding Kim’s birth. Bottom line: Kim is lucky to be alive…she is lucky that her life turned out the way that it did. So many children died in the Vietnam war. Just because they were children didn’t mean that their lives were spared. This made it that much harder to realize that Kim was a child of war. Who knows what could have happened to her. So much happened during the Vietnam war and I don’t think Kim nor I had a handle on what the American relationship with Vietnam was during the war.

The end of the night was the best. We got an opportunity to spend the night with the children of the orphanage. Kim and I used rice paper to make our own spring rolls, sat with a family that shows more love that we have ever seen, and played a new card game that Americans wouldn’t understand. Immediately we felt a part of this home… we wished we could stay longer when we left. The children embraced us. The night was full of laughter and games and culture.

The orphanage is a home we couldn’t imagine experiencing. Suzanne, the founder, is an amazing influence in the lives of these children. As teachers, one can only hope a child loves them this much outside of their biological parents. Kim cried leaving. The kids told her this was a “see you later,” not a “goodbye.” They are one of the biggest reasons we are here and cannot wait to share [the experience] with our students.”

This fall, both Kim and Amanda will lead students’ personal research projects modeled after this fellowship.

“We will use this fellowship to inspire our students to have a strong sense of self and to celebrate and appreciate different cultures, religions and customs of others,” wrote Amanda and Kim in their grant proposal. “Through this research, students will understand their heritage through geography units; we will also embed a heritage lesson for students to understand how heritage shapes who we are.”

Additionally, the teachers plan to continue student fundraising efforts begun last year to benefit the Allambie Orphanage, and instigate pen pal relationships between children living there and students. For a community-wide multi-cultural night, families will be invited to share traditions and food from their cultures.

“Heritage is important,” said Kim, “because it is the basis for who we are, the choices that we make and the connections we have with other people. Together in the classroom, we will focus on my cultural background as a lens to understand the diverse backgrounds of each other.”

Follow their fellowship on the Facebook page created for their students and their complete fellowship report here.