Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, a historic event that occurred in the town where Kyle Peaden taught students who knew nothing about it. We are grateful he shared his design process that led to his fellowship and its outcomes…

In my 2012 Fund for Teachers grant proposal, I wrote:

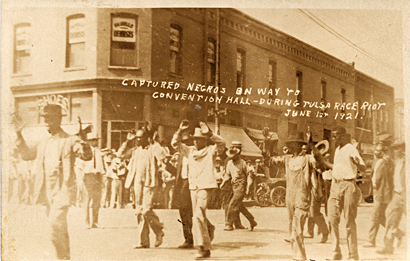

I see history repeating itself. I see that my students do not know or comprehend of the hate and bigotry that violated our city in the early 20th century in what is regarded as one of the most destructive race riots in the 20th century. While my students may not be involved in the repulsive actions of racist groups of individuals in the past, I can see hints of the same distance from understanding. Students are letting bullying and anger fill the voids where communication, discussion, and understanding should be. I hope to bring about understanding of racism, hate, and intolerance by contrasting the history of South Africa to the history of our city. By visiting South Africa to show the history and recent developments in Apartheid and segregation I can bring students to look closer at their own local history. This quiet city holds scars and wounds from one of the largest race riots in America and it remains a difficult subject to face. These wounds are ignored, and the impact of the race riots still linger. By bringing students to my experiences in South Africa I believe they will be able to use an unbiased process of examination to the history of South Africa and eventually to our history.

Sometimes it is too difficult for a child to think that something so awful could have happened in their home town. A sense of favoritism holds strong in their heart that would leave them less willing to hear or realize what happened here not too long ago in their own backyard. It is my hope to go to South Africa to learn firsthand why one person can do terrible things to another and how the goodness in humanity can prevail. I hope to bring a community of students closer to understanding what did happen, what can happen, and what we can do to make sure none of that will happen here ever again. By looking at examples of strength, ignorance, and hope abroad in South Africa and right here in our own back yard these students will work through questions dealing with morality and morality that can help their own understanding of such subjects.

My exploration started at home in Tulsa. I wondered how a city could recognize and reconcile the immense tragedy of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. This question took me on a journey over 8,700 miles away to South Africa. South Africa is a country that exemplifies the evils of racism and the hope that can bring a society from those dark times. I wanted to study the culture of South Africa, its art, food, and people, so that I could gather a greater understanding of what happened and how the country has adjusted from Apartheid.

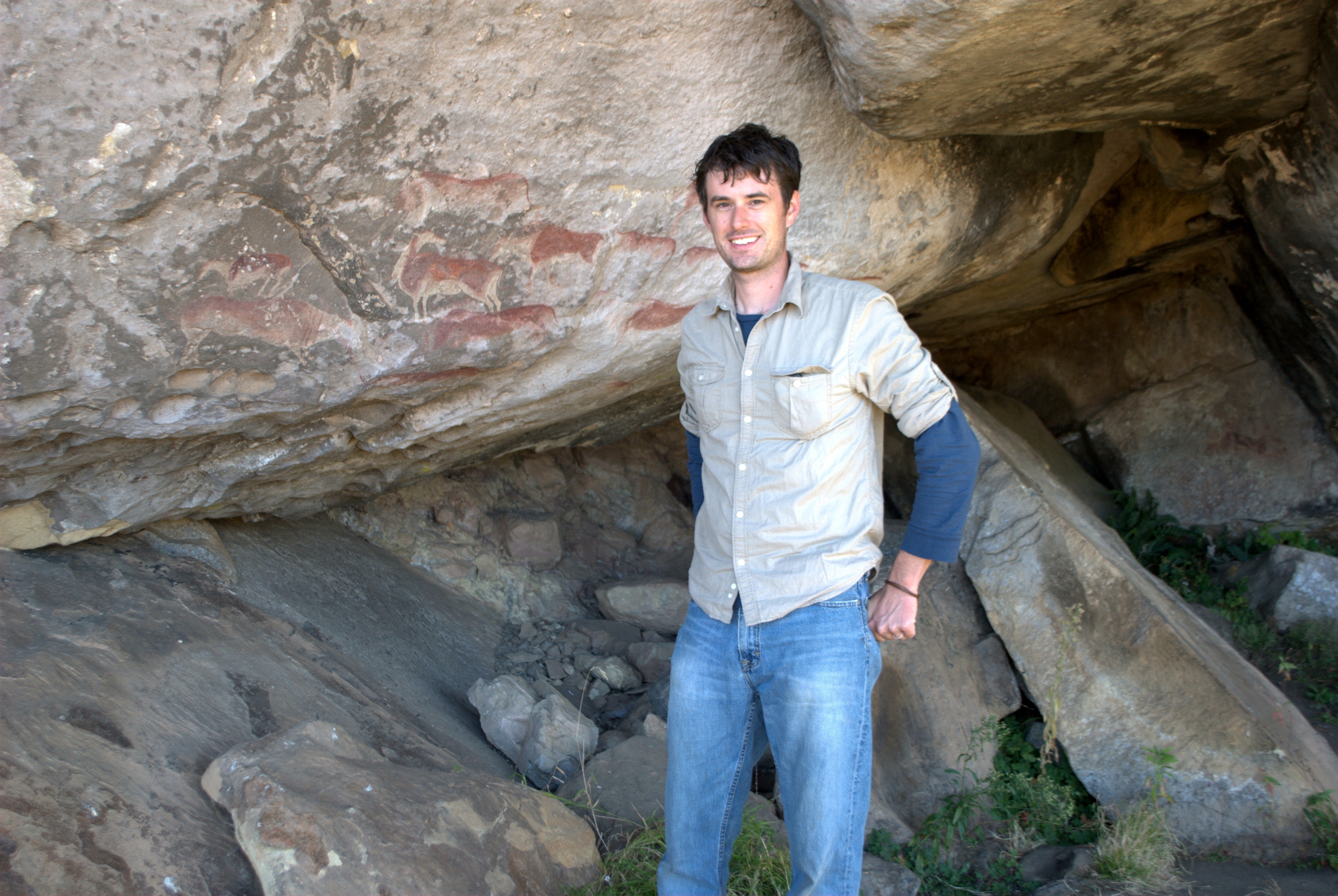

My journey began near Johannesburg where I spent a week in Soweto, the largest and arguably most influential townships during the resistance against Apartheid. During my stay I met the most welcoming people during my whole stay in Africa. I couldn’t resist the opportunity to teach a lesson at a local art school as soon as I found one and my work with Emilia Potenza, the curator at the National Apartheid Museum, gave me a greater background understanding to the reasons and history behind Apartheid. Not far from this epicenter of struggle I visited the Cradle of Humankind where the fossilized remains of our direct ancestors are found. From Johannesburg I traveled through Kruger National Park driving amongst natures most raw surroundings to the Drakensberg Mountains. The Drakensberg site is home to thousands of Bushmen paintings throughout the mountain ranges. After hiking and documenting these ancient works of art I continued south toward the Cape of Good Hope.

In Cape Town I visited the many cultural and historical sites that represent so much of this diverse country. The blend and recognition of cultures reminded me so much of the country I grew up. I started to understand and recognize the steps towards reconciliation in South Africa and a small step to what might be needed at home. The art and history of this wonderful country helped me to see what steps my students and I can take to repair and resolve our troubled past. While my journey is a personal one, I know that the impact of my steps and my efforts will help students to further their own passage through the difficult topics of race, racism, hate, and hope. In my exploration our dark history nearly broke my heart, the people of South Africa filled it with joy, and my students carry it forward with hope.

I stayed in Tulsa teaching for another two years and my wife and I moved to Wisconsin. I ended up working with the Title I program at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction because I felt like much of what I learned is the systems and structures established during Apartheid had some of the deepest impacts on South Africa and the black community of Tulsa. I wanted to work on addressing those policies and by working at the state level I could work towards a more equitable education system.

My Fund for Teachers experience has helped to inform the decision making and policies in programs I work with. By acknowledging the impacts of multiple landscapes and their relationships with race I am more prepared for the injustices that our youth face. Wisconsin has some of the largest gaps for students of color and our state agency has made the work of closing those gaps one of our highest priorities. Personally, I work not only with Title I-A but in programs that support incarcerated students, students that are placed in foster care/out-of-home care, and I am a part of some of the equity work occurring in our agency. I’ve worked on teams that developed and train all staff in our agency on equity to build a foundational experience for our work. I think it is from the experiences in South Africa, learning from the Apartheid museum, the cradle of humanity, Soweto, and the people (most importantly the people!) that could tell their story that helped me build an understanding of how I can listen and work towards a more equitable education system for all our students.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Kyle recommends the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation as a starting point for those wanting to know more about the Tulsa Race Massacre. He also encourages us all to reframe language you might hear this week referring to the event as the Tulsa Race Riots. “I’ve learned since my fellowship that the word riot incorrectly places blame on Tulsa’s Black community, which acted in response to an unlawful arrest and subsequent rounding up of 6-8,000 Black Tulsans – many for up to eight days,” he said.