Barbara Walters said, “Most of us have trouble juggling. The woman who says she doesn’t is someone whom I admire but have never met.” FFT Fellow Helen Dole, however, seems to be managing fairly well. Helen teaches sixth grade at Lower Manhattan Community Middle School in New York City. With her teammate Molly Goodell, she and five-month-old daughter Sophie Tilmant set off for Alaska this summer to tour boreal forest, coastal, tundra, and glacial ecosystems and collect first-hand evidence of climate change for a sixth grade unit called Human Impacts. She shares some of her experiences below…

Why was it vital for you to pursue this particular opportunity/experience?

An educator in Denali shares with us about the methane that is being released as a result of permafrost melting.

We teach in a school that has students from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds. Some students have second homes in the Hamptons, while others have grandparents/aunts/uncles cousins all under the same small roof in Chinatown. We previously did a Human Impact project; students relied on internet searches to source information. Now we have brought real data; photos, interviews, and our stories to ALL of our students–we are bringing the world to them even if they have yet to board a plane.

I now see the bigger picture in a deeper way and I’m more passionate about making my students ‘see’ it, too. It’s easy to read articles about climate change and cognitively understand what is happening. It’s an entirely different boat to stand by the sign showing where a glacier was just 10 years ago (and now it’s ice-free) and not viscerally feel how the world is being affected.

Why was this opportunity transformative for your teaching on a macro-level?

On our heli-hike adventure, we learned how about it’s not how warm it is, but rather the length of the growing season that is changing the vegetation.

Teaching is a joy and a grind. You are always “on;” engaging with students in person, families via email, via google docs with colleagues, or in person at staff meetings. This opportunity allowed me to turn my brain to a different mode from the regular routine. I was learning, yes, but in a more open and unencumbered way than the minute-by-minute schedule of a middle school environment. I landed back in NYC feeling enriched and invigorated for the year ahead.

Also, we experience the world through storytelling and now, our stories are going to be much richer and more vivid; filled with cutting edge science and personal anecdotes from our time in Alaska. They will be able to cite specific examples — equisetum plants spreading, the number of days above 50 degrees Fahrenheit North of the Arctic Circle, soil that doesn’t hold rain, roadways decimated from melting permafrost, increased frequency of wildfires, heavier snowfalls in winter, methane gas being released at an alarming rate, the list goes on — and then have teacher stories/images to connect to these sometimes hard-to-internalize science facts.

How did your fellowship changed your personal and/or professional perspective?

In 2010, the ice used to be where we’re standing.

I went into this fellowship with the understanding that I was traveling with my co-teacher, Molly, and that we would strengthen our co-teaching skills on this trip. I didn’t know how much so, though! I traveled with my 5-month-old infant, so I relied on Molly in SO many ways for support and sanity. This journey to Alaska was like the ultimate trust-builder. If students thought we completed each other’s sentences BEFORE this trip, now they’re going to think communicate telepathically!

Additionally, living in a city, it is easy to go about my day and not feel fundamentally affected by climate change. My food, my transportation, my workplace, and home are all far enough removed from Mother Earth that I am not forced to see how climate change is a real thing affecting real people, animals, and plants. On this fellowship, I was able to witness how ice has shifted, plants and animals have migrated, and people have altered their ways of life because of a warming planet.

-

-

Barrow, Alaska. The road stops here; any further North and you’re in the Arctic Ocean.

-

-

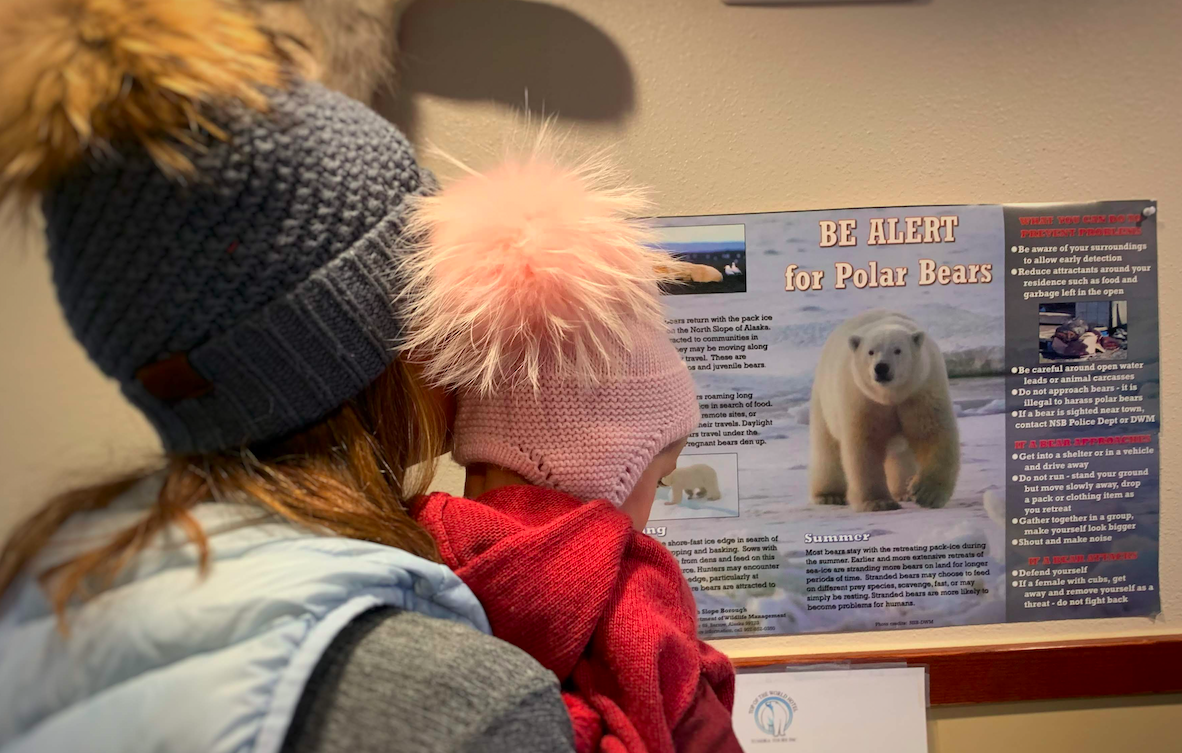

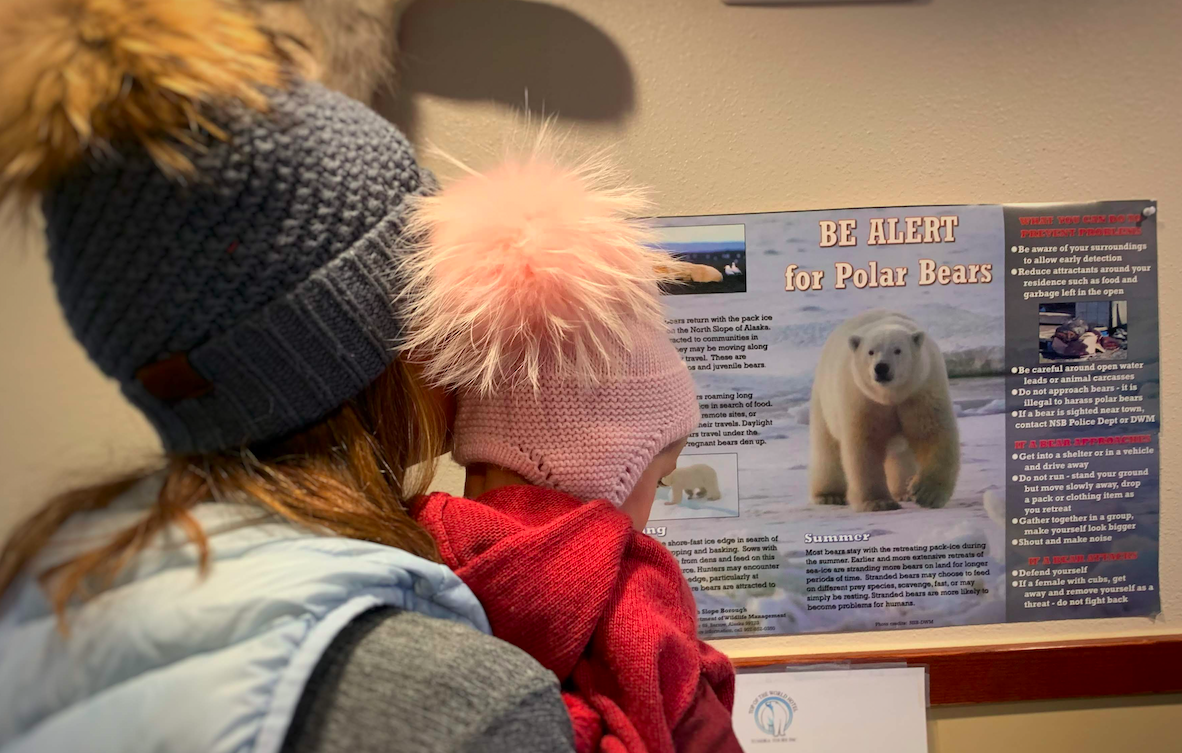

Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What do you See? We saw signage for polar bears, but only saw a black bear in real life. She was panting because it was too hot for her!

And finally, what we’re all here for…What did Sophie think?

I’m so glad she was able to come. Even though she won’t remember it; I can show her the pictures and later tell her about it. There were challenges; being a NYC baby she wasn’t used to being in a car seat, so I had to sit in back with her while my co-teacher, Molly, drove because Sophie was fussy in the car seat. And we had to find a babysitter for the day we kayaked, but we found a kind local woman in Seward who watched her and did a great job; even sending me photo updates. She was a big fan of the helicopter ride to the subalpine arctic tundra; smiling the entire way!

When we applied for a

Fund for Teachers grant I knew I was expecting, but figured we should go for it anyway. When she arrived AND we got the fellowship I realized I’d still be breastfeeding so wanted to bring her along. My co-teacher, Molly, was a wonderful sport and supported me in so many ways–driving, carrying Sophie on parts of the hikes, and dealing with lights out in our room at 8:30pm–amongst other things. Hah! Overall, she was a pretty easy baby for the trip–not too many tears or too much fussing which allowed me to enjoy the learning adventure I was on! Happy momma = happy baby.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Helen is in her 15th year of teaching. She is a New York City Teaching Fellow, Math for America Master Teacher, and former Department of Energy Teacher as Scientist. She believes in helping students to see science in their everyday lives; continually striving to make connections between their world and the science they are learning about. Outside the classroom she is a passionate runner. She’s a proud mom to two young children.

Helen is in her 15th year of teaching. She is a New York City Teaching Fellow, Math for America Master Teacher, and former Department of Energy Teacher as Scientist. She believes in helping students to see science in their everyday lives; continually striving to make connections between their world and the science they are learning about. Outside the classroom she is a passionate runner. She’s a proud mom to two young children.

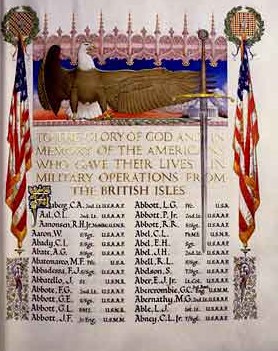

“When applying for the Fund for Teachers grant, I researched my grandfather’s military service and his path from Nebraska to Normandy,” said Dan. “On D-Day, he flew the Boeing B-17 with the USAF 94th squadron from the

“When applying for the Fund for Teachers grant, I researched my grandfather’s military service and his path from Nebraska to Normandy,” said Dan. “On D-Day, he flew the Boeing B-17 with the USAF 94th squadron from the

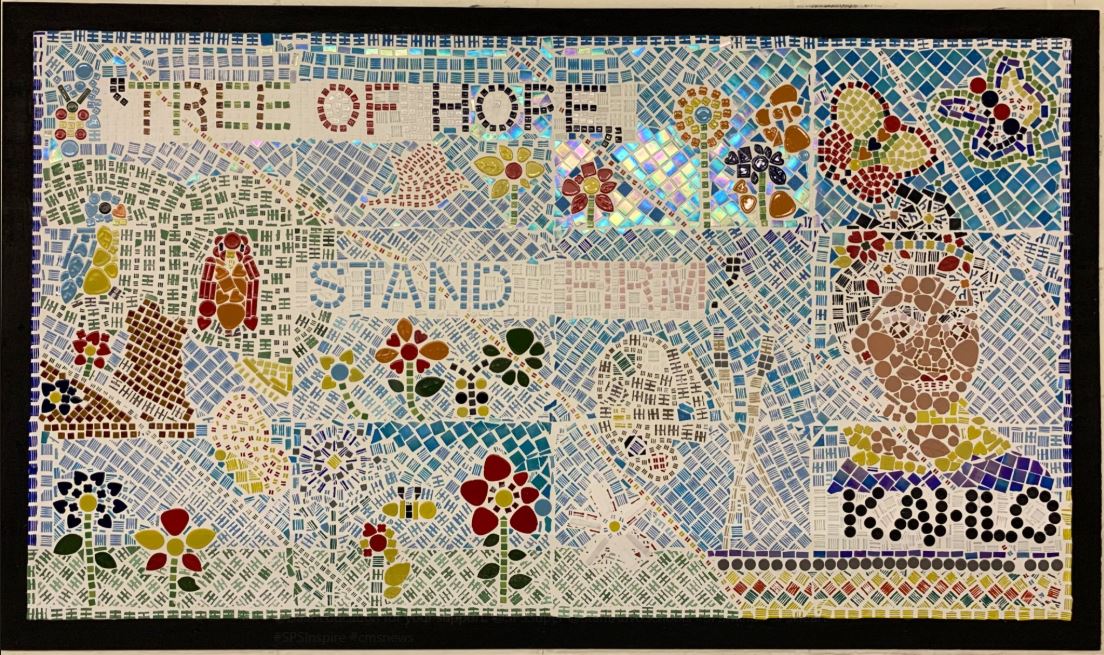

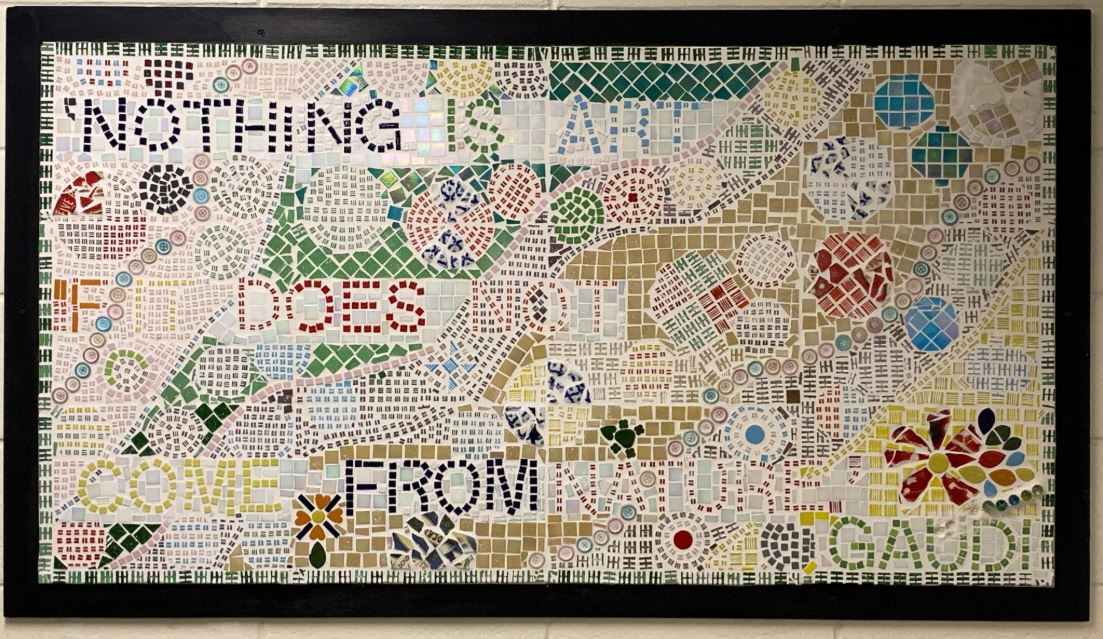

Tammy has taught for 29 years, first with special education, then third grade, middle school Language Arts, and now Fine Arts. Recently she received a Spotlight Award for Teachers, one of 20 recipients nominated by peers and awarded from across the Stamford Public School district.

Tammy has taught for 29 years, first with special education, then third grade, middle school Language Arts, and now Fine Arts. Recently she received a Spotlight Award for Teachers, one of 20 recipients nominated by peers and awarded from across the Stamford Public School district. The students I teach represent a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds, many of whom rarely even leave the county. Their ability to conceptualize the vastness of our country, and our country’s resources is very limited, making it difficult to grasp the scope and initiatives involved in the

The students I teach represent a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds, many of whom rarely even leave the county. Their ability to conceptualize the vastness of our country, and our country’s resources is very limited, making it difficult to grasp the scope and initiatives involved in the