Thanks to FFT Fellow Tim Barry for his reflection on his two Fund for Teachers fellowships inspired by students’ curiosity and focused on elevating the experiences of Native Americans during World War II.

I am in my sixteenth year as a Special Education Teacher and have spent fifteen of those years teaching middle

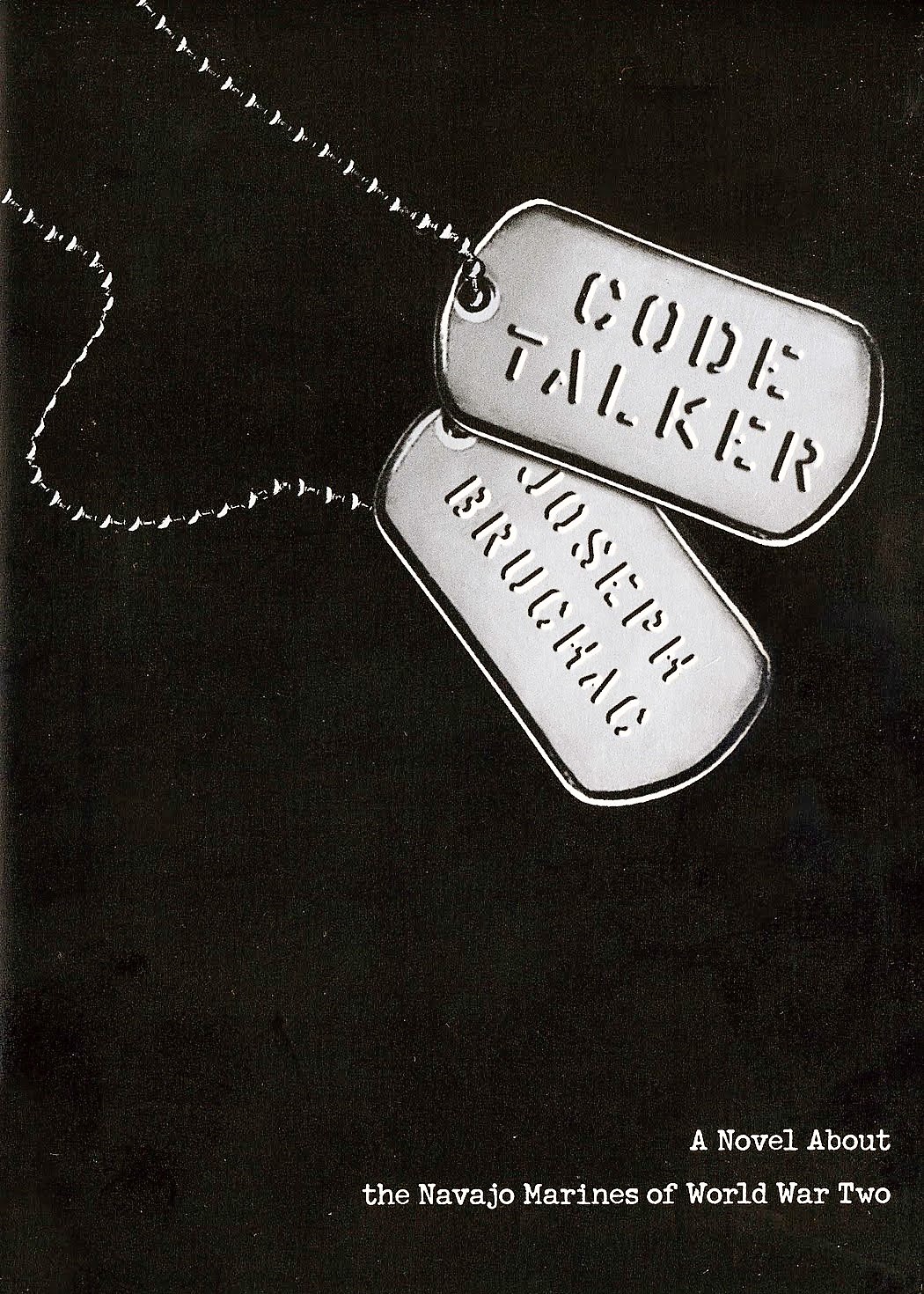

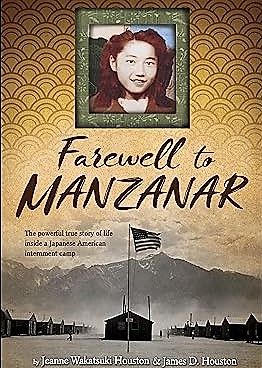

school. Based on students’ needs, much of my time is spent teaching and supporting students in English and social studies classes. Our 7th-grade students read Code Talkers, by Joseph Bruchac and Farewell to Manzanar, by Jeanne Houston as part of our English curriculum that explores the importance and impact of identity. In 8th grade, we read All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque. The beauty of this subject matter is that it fosters intellectual curiosity in our students. They want to know more, they want to ask questions, and oftentimes, these questions create dialogue and a spirit of inquiry that extends into authentic, teachable moments.

As a student of history, I am very familiar with the Pacific and European Theaters of World War II. Admittedly, the story of the Navajo was one that I was aware of, but not well-versed in. When reading Code Talkers, the idea that is most foreign and confusing to our students revolves around “why?”

Why would the Navajo be so loyal to a country that attempted to erase their culture? Why would these people be willing to save the country, with nothing in return?

As Code Talkers is our students’ first introduction to the World War I & II subject matter, it is the ideal opportunity to take an anchor text and extend the discussion beyond the pages of a book. This is not just a story of what the Navajo did, but an introduction to WHO the Navajo are. This fellowship provided me with an opportunity to gain first-hand knowledge of how their culture and identity impacted their role in World War II and bring back an authentic experience to the students.

- From Tim’s first fellowship at Memorial at the Amache cemetery.

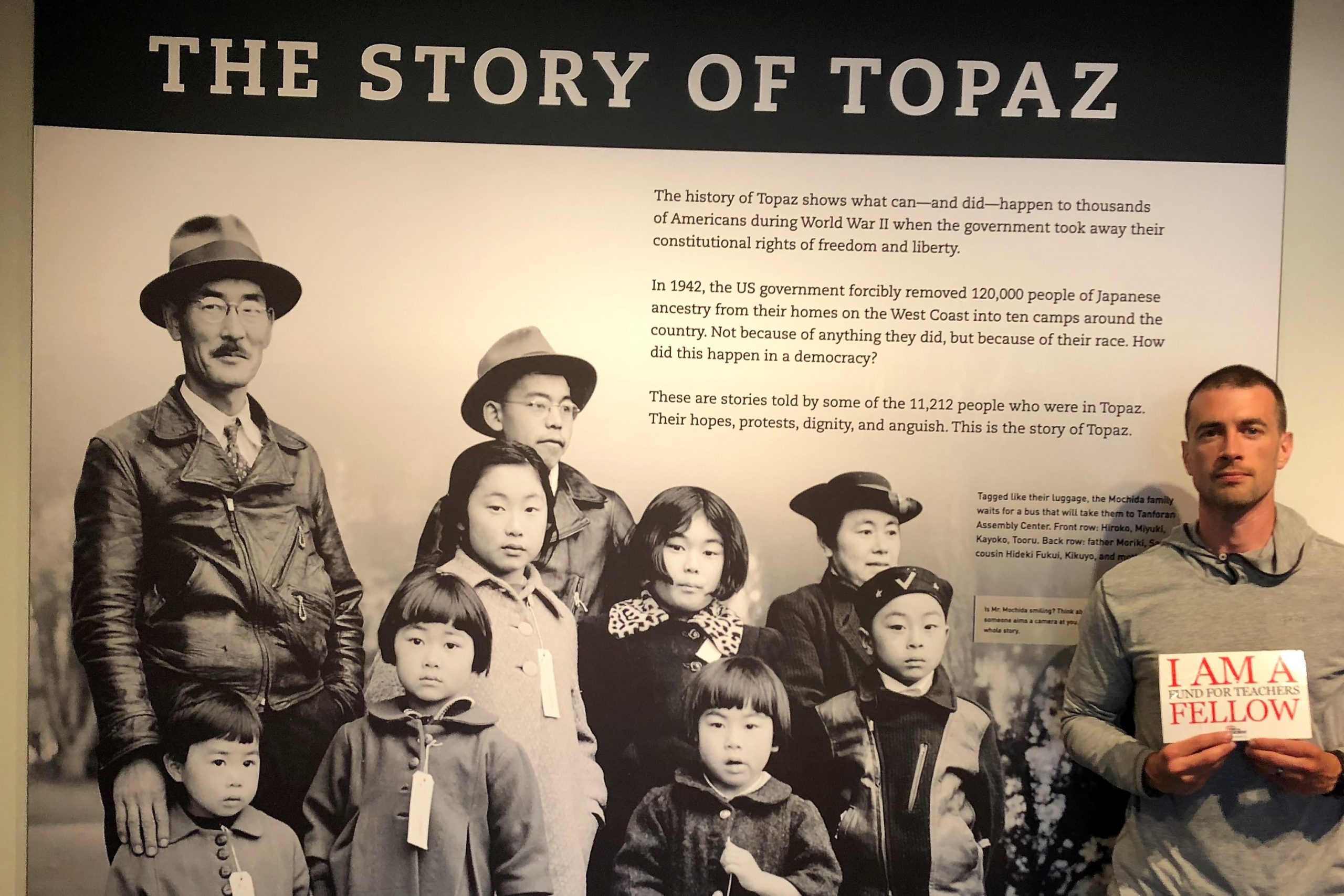

- Also from the first fellowship Topaz Museum in Delta, UT

Having previously completed a Fund for Teachers fellowship to Manzanar in 2018 to examine life in and around Japanese Relocation Camps in Utah and Colorado, I was awarded a second grant last summer to engage with the Navajo Nation in Arizona and New Mexico. I examined the importance of cultural identity and explored how that identity empowered them to overcome marginalization by the U.S. Government and embrace the role as Code Talkers in World War II.

Read more about Tim’s 2023 fellowship here.

The highlight of my fellowship was hearing Peter MacDonald speak at the National Code Talkers Day event. Mr. MacDonald, at 94, is the youngest of the three living Code Talkers. He told the story of his enlistment at the age of 15 and the pride he felt in being Navajo and wearing the Marine Corps uniform. During his speech, he implored the Navajo youth to continue learning, protecting, and using the Navajo language despite its challenges because language is the key to sovereignty.

As I spoke to members of the Navajo Nation, I began to question my qualifications to teach about the Code Talkers’ story. This was not due to any unfavorable reception of my fellowship; quite the opposite, everyone I interacted with was welcoming and willing to share their knowledge. My concern revolved around doing justice to their culture, community, and the Code Talkers. Ultimately, it will drive me to deepen my learning and seek experts to share their stories.

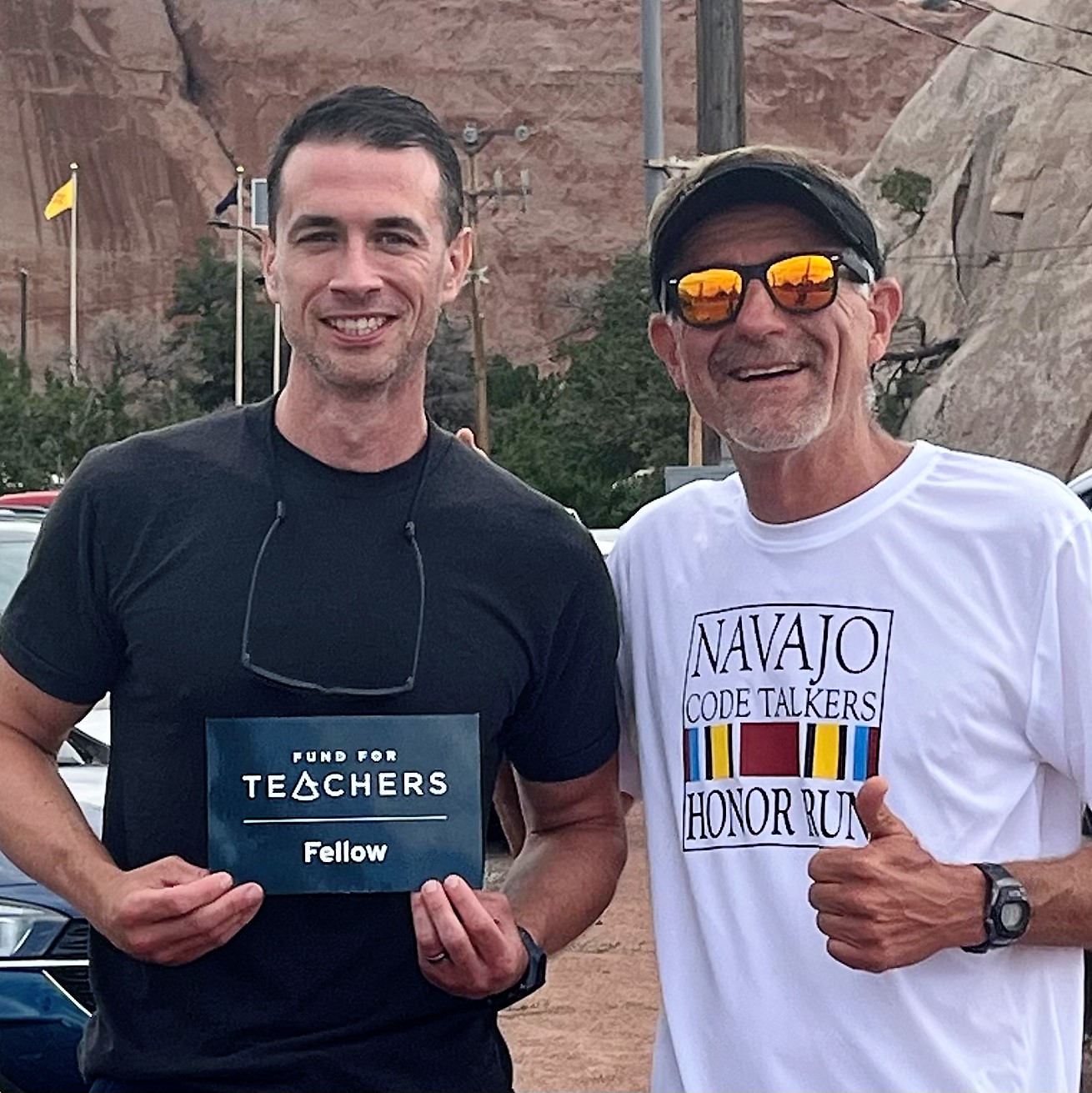

- With NavajoYES Director Tom Riggenbach

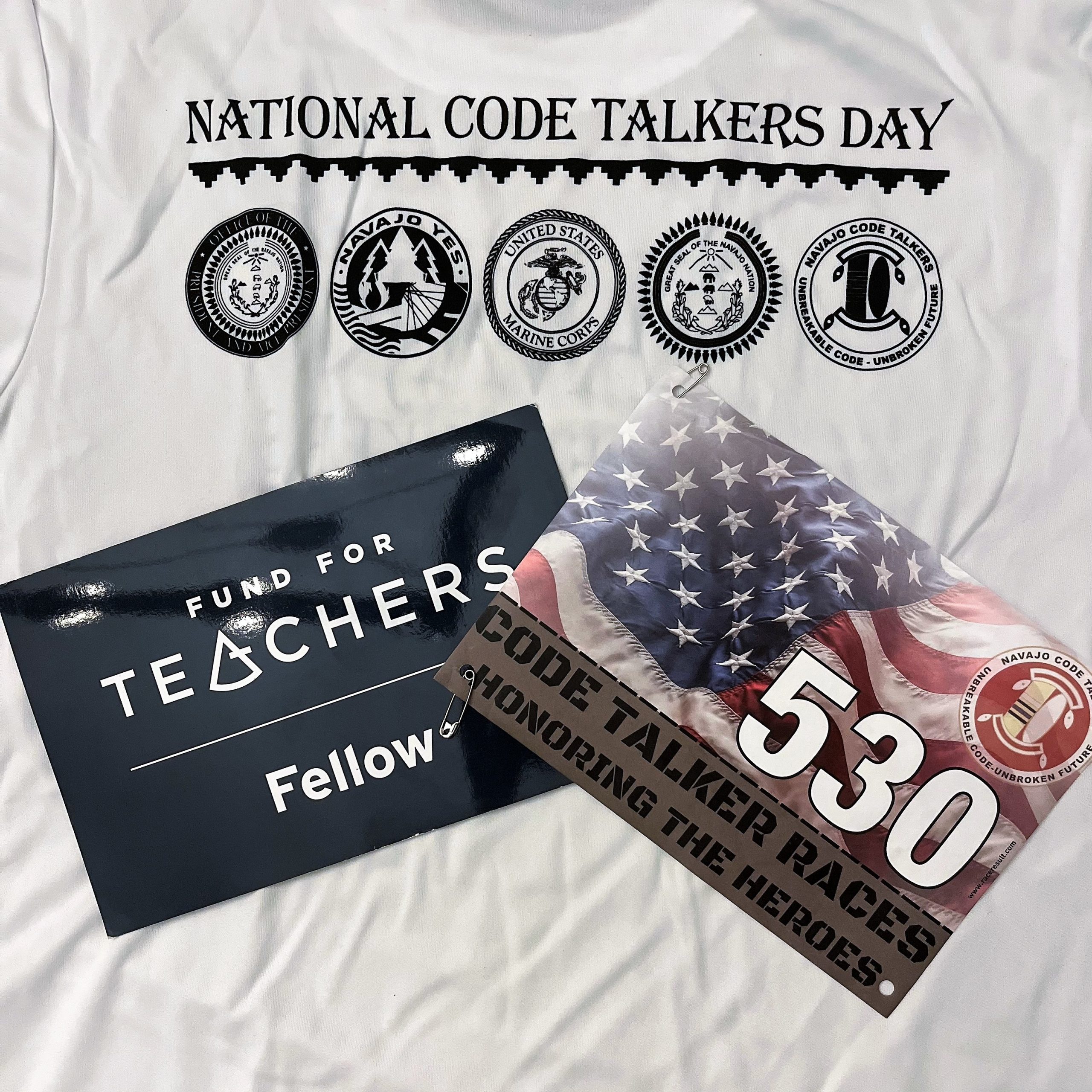

- Code Talkers Day Honor Run

The experiences I returned with have allowed me to provide authentic insight and perspectives to increase and enhance my students’ comprehension within our Code Talker unit. I gathered a variety of vetted, leveled texts to enrich academic discussions among students of varying ability levels. Most importantly, I have created relationships with people who can offer a cultural background vastly different from my students and foster a climate of understanding.

My Fund for Teachers fellowship reinforced the importance of self-discovery and lessons presenting themselves. My experience initially concentrated on enhancing my understanding of Code Talkers, which evolved into a story of the preservation of language, culture, and identity that is still challenging today.

When experiencing new cultures, we cannot rely solely on academics studying from a distance. It is critical to interact with communities directly to ensure that shared knowledge is culturally relevant.

Additionally, the fellowship enhanced my desire to explore and foster a sense of intellectual curiosity with my colleagues. The opportunity it provides for teachers to enrich their learning and share the inspiration of self-study rekindles much of the excitement that brought many of us into teaching.

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with