“We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body. This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present.”

“We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body. This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present.”

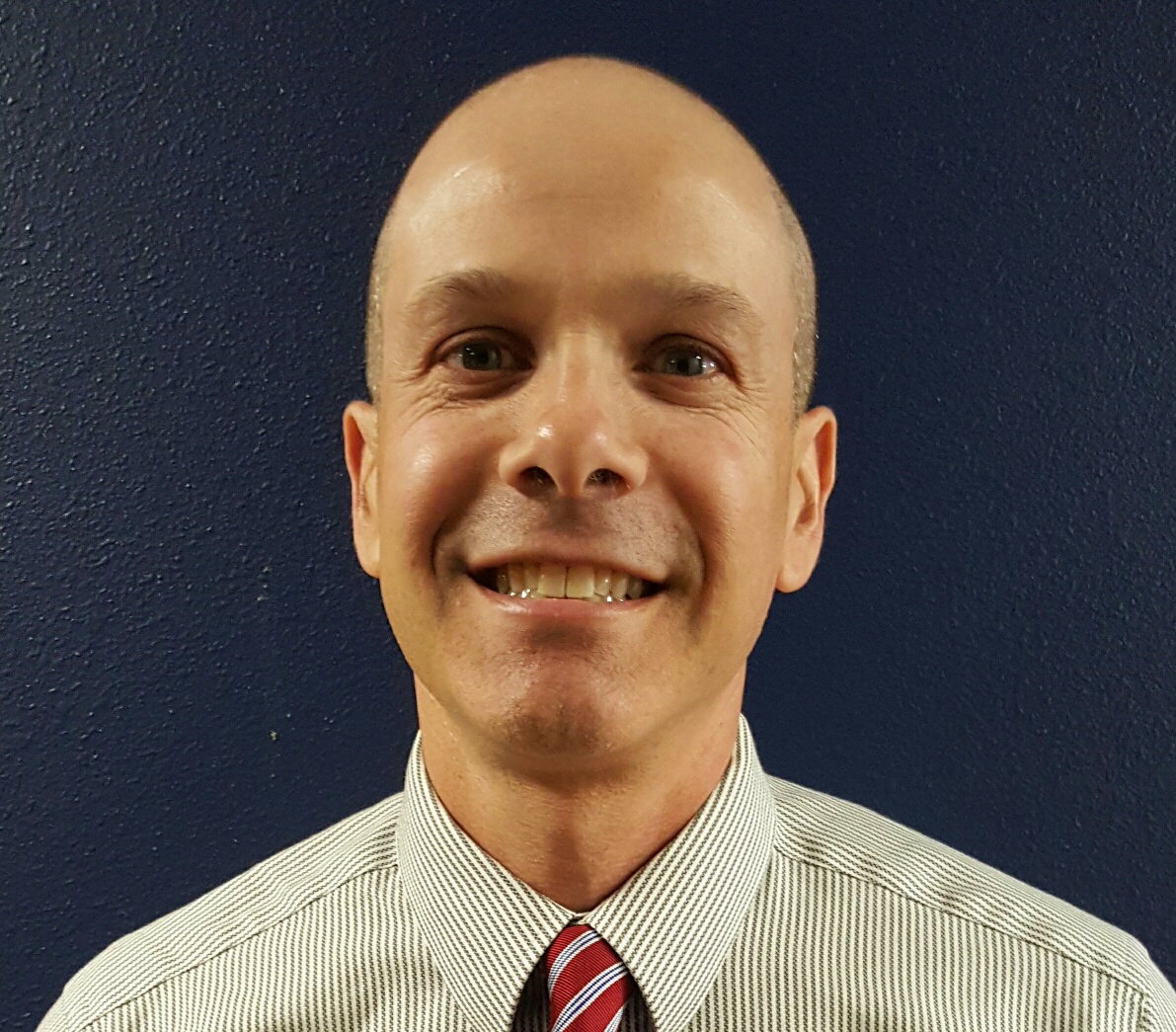

This excerpt from New York Times bestseller The Body Keeps the Score resonates with Michelle Moyer and her students for different reasons. During Michelle’s fifteen-year career as an elementary teacher, she experienced domestic abuse and subsequent diagnoses of Multiple Sclerosis and breast cancer. Her second graders at Mohegan Elementary in Uncasville, CT, also exhibit physical symptoms of trauma caused by a different set of issues, including:

• being bullied by sibling with no adult intervention

• witnessing arguments and verbal abuse between divorced parents

• fear of caregivers, and

• parents’ substance abuse and serious health issues.

“Due to my own life experience with trauma and anxiety, I can identify and understand many of the [trauma-induced] behaviors the students are exhibiting,” wrote Michelle in her grant proposal. “I know the challenges and difficulties associated with processing and moving past these feelings and I want to help my students successfully conquer, or in the very least, begin their journey to conquer them.”

Their mutual path to wholeness involved a Fund for Teachers grant and a rowboat.

Last summer with a $5,000 grant, Michelle learned to row a single shell on lakes in Italy. She designed this unique fellowship to engage in personal trauma recovery as a role model for students with trauma and to revise a social-emotional learning (SEL) curriculum using skills and strategies learned to build a safe, supportive classroom community.

Rowing with a local club was already playing a role in Michelle’s recovery. The activity aligned with the four steps to trauma recovery documented in Dr. Jennifer Sweeton’s book Trauma Treatment Toolbox by:

- Providing a safe space of acceptance and individuality;

- Fostering community, healthy connections, and a sense of belonging;

- Helping to realign emotional systems, and;

- Igniting a new self to dream and hope for a joyful and successful future.

Designing this particular fellowship was the next step for her and her students.

“My fellowship provided intensive, guided instruction with a one-on-one coach designed to focus on skills such as self-trust, risk-taking, adapting to unfamiliar circumstances, physical challenges, asking for help, receiving constructive criticism, trusting someone else, potential trauma triggers, and facing failures,” said Michelle. “It encompassed the same four steps I want my students to experience, so this grant supported my own journey through trauma to inform and increase understanding of my students with trauma.”

“My very first day of rowing, was in a coastal boat, which I had zero experience in. I was soooo nervous!” she said. “It was also one of the hottest days of the summer. Being nervous, and now fearing my MS may come into play due to the heat, I hesitated. I paused, took some mindful moments, processed my fear, and said ‘I will NOT allow fear to take this from me.’ I got in the boat. Acclimating to the boat, I began to row. I began to row strong! Best Rowing! Best Rowing! the Italian coach cheered!”

- BEST COACHING Canottieri Luino!

- See the Club, meet my team!

Michelle is now modeling for her students what resiliency and healing look like. She’s also refining an SEL curriculum that includes specific activities to help students begin to think about, define, and create a positive self-identity.

“I want to show them the possibilities truly are endless for their young selves, IF they ALLOW themselves to try!” Michelle said. “Through journals, role play, read alouds, discussions (I researched, bought, and organized many new books), and relationships (making sure I dedicate time to talk and listen to each student), I am committed to connecting and discovering the needs of each student.”

She is also leveraging her personal growth to see her students through a new lens and guide a pedagogy switch from behavior management to behavior modification. “No more reacting to behaviors,” she said, “but leaning-in to them with the student to understand ‘the why.’”

“Through therapy, personal reflection, and exercise I am only now discovering myself, my authentic self,” said Michelle. “It has been a long and difficult journey, but very rewarding. One that equipped me to help my students on a new level — especially vital in this new world of pandemics. I want to be that one person, that one place, where my students have the chance to find out how the beautiful the world really is!”

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Michelle Moyer is a second-grade teacher who has taught in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. She believes teaching and learning in the elementary classroom should be meaningful, integrative, value-based, challenging, and active. Michelle empowers her students through comprehensive SEL and restorative practices, collaborative environments, and high standards. A teacher for 15 years, her career accomplishments include being an FFT Fellow and earning a master’s degree in education.

Michelle Moyer is a second-grade teacher who has taught in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. She believes teaching and learning in the elementary classroom should be meaningful, integrative, value-based, challenging, and active. Michelle empowers her students through comprehensive SEL and restorative practices, collaborative environments, and high standards. A teacher for 15 years, her career accomplishments include being an FFT Fellow and earning a master’s degree in education.