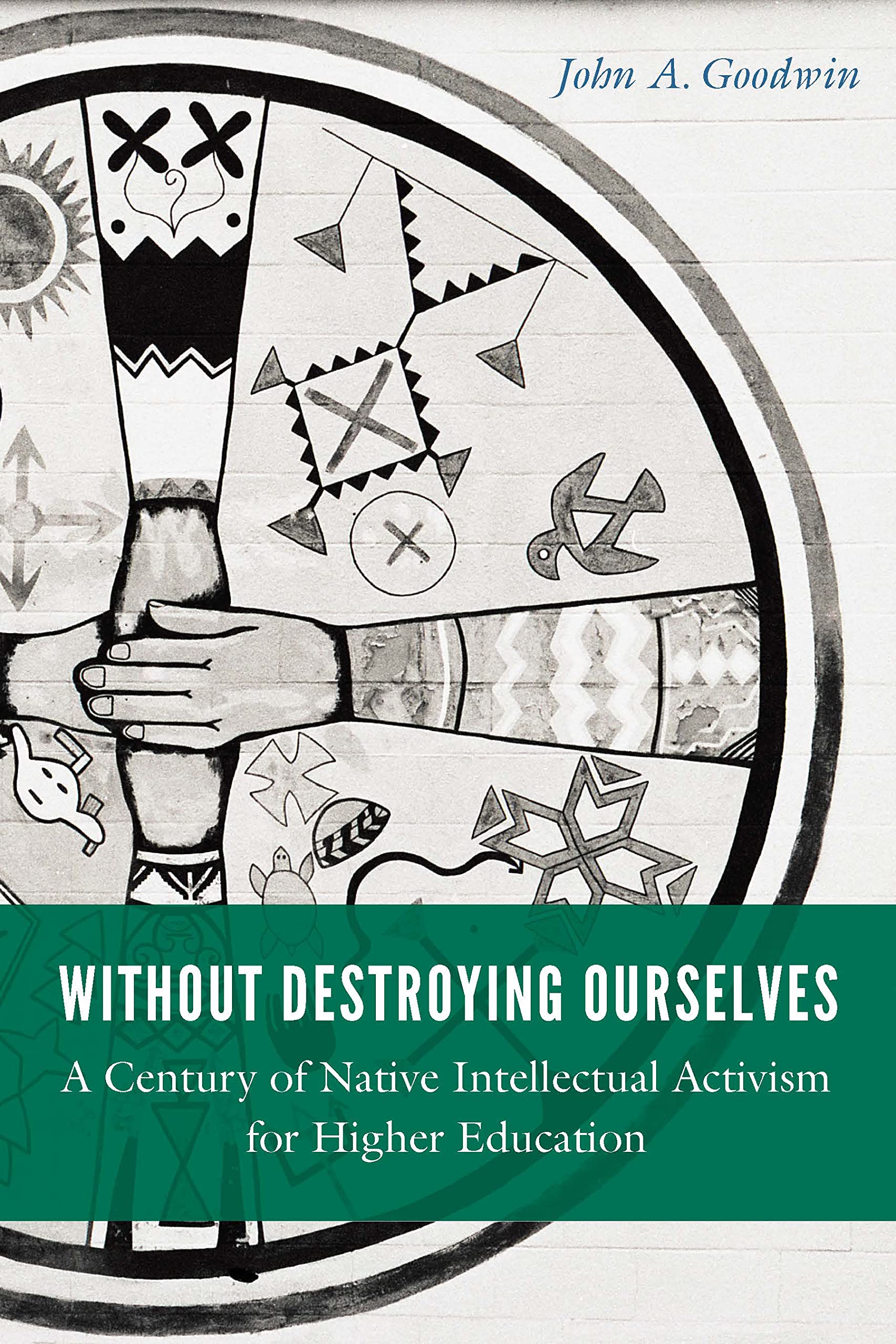

Today, millions of people received a “Breaking News” alert from The New York Times with the heading: “Over 500 Native American children died at U.S. schools where they were forced to live between 1819 and 1969, an initial federal inquiry found.” This is old news to FFT Fellow John Goodwin, who teaches U.S. History, Native American History, and an interdisciplinary research and writing course at BASIS Phoenix. In March, his book Without Destroying Ourselves: A Century of Native Intellectual Activism for Higher Education was released and this summer he will further his research to increase students’ exposure to diverse primary history sources.

Today, millions of people received a “Breaking News” alert from The New York Times with the heading: “Over 500 Native American children died at U.S. schools where they were forced to live between 1819 and 1969, an initial federal inquiry found.” This is old news to FFT Fellow John Goodwin, who teaches U.S. History, Native American History, and an interdisciplinary research and writing course at BASIS Phoenix. In March, his book Without Destroying Ourselves: A Century of Native Intellectual Activism for Higher Education was released and this summer he will further his research to increase students’ exposure to diverse primary history sources.

With his Fund for Teachers grant, John will conduct research at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington DC to build two project based learning experiences that raise awareness of Indigenous experiences at American Indian boarding schools and enhance the physical and digital presence of one such site in Phoenix.

“So much of Indigenous history is understandably viewed under a dark shadow of colonialism, with all the violence and dispossession that comes along with it,” wrote John in this blog post. “It can be difficult, especially for young students, to work through a careful study of this history with any sense of optimism left. And yet, if we look closely at the words and actions of Indigenous people themselves, we still see it. We see not only a bare sense of resilience and survival but at times a true optimism and an infectious energy that comes from leaders’ ability to highlight and target shared opportunities for growth within struggle.”

The first phase of John’s fellowship will include documenting content and artifacts at the NMAI and taking advantage of the archival databases at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, MD and the National Archives. Afterwards, he will conduct additional research at Phoenix’s Heard Museum before heading to Fort Lewis College in nearby Durango, CO — a four-year college that once served as an American Indian boarding school.

The first phase of John’s fellowship will include documenting content and artifacts at the NMAI and taking advantage of the archival databases at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, MD and the National Archives. Afterwards, he will conduct additional research at Phoenix’s Heard Museum before heading to Fort Lewis College in nearby Durango, CO — a four-year college that once served as an American Indian boarding school.

“Using my catalog of observations, images, narratives from visitors, and archival documents in the subject area, I will curate a large collection of materials that will transform the capstone project experience for my students,” wrote John in his grant proposal. “Specifically, students during the final 5 to 6 weeks of the course will work in groups to develop proposals for action that use these public history sites as models, with the goal of improving the Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center, once an American Indian boarding school.”

While today’s news alert elevates once again the tragic experiences of Native American children and their families, John also sees a story of growth and resilience within struggle.

“A lot of the students who went through those schools went on to be leaders in their communities, and in fact in a wide range of American settings, both Native and non-Native spaces,” he said when we reached out to him today. “Often they did so while still maintaining tribal languages and cultural connections. I think the students I teach—and probably most American students—can really learn from those types of stories. I think those stories keep us tapped into what is best and most intriguing about our identity as Americans, without white-washing it or unnecessarily painting it through rose-colored glasses. And for our students here in Phoenix, I see the boarding school site as an often overlooked location that could be highlighted and enhanced as a public history site for students and the wider community.”

Top photograph courtesy of Colorado Public Radio News.