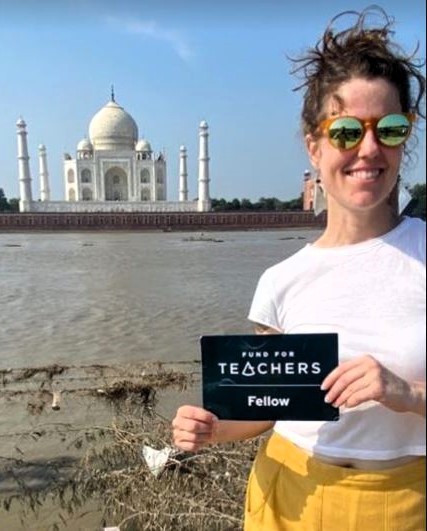

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we share the teaching of Neha Singhal (Montgomery County Public Schools, MD). In one of our more unique fellowships, Neha conducted mini-ethnographic research on the experiences of doulas and other birth workers in New Delhi, India, to increase IB Anthropology students’ understanding of fieldwork and data analysis, and to spark interest in maternal health justice in the United States. Neha exemplifies what can happen when teachers are given the trust to design experiential learning. She combined her educational background (an undergraduate degree in international business, international development and conflict management and a master’s in social justice), previous experience (work with a non-profit on the Texas/Mexico border), and a passion for women’s health to create in-depth, project based learning for students.

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we share the teaching of Neha Singhal (Montgomery County Public Schools, MD). In one of our more unique fellowships, Neha conducted mini-ethnographic research on the experiences of doulas and other birth workers in New Delhi, India, to increase IB Anthropology students’ understanding of fieldwork and data analysis, and to spark interest in maternal health justice in the United States. Neha exemplifies what can happen when teachers are given the trust to design experiential learning. She combined her educational background (an undergraduate degree in international business, international development and conflict management and a master’s in social justice), previous experience (work with a non-profit on the Texas/Mexico border), and a passion for women’s health to create in-depth, project based learning for students.

My high school was only the second school in our district (the largest in the state) to offer IB Social & Cultural Anthropology and has become one of the few schools in the country to offer such a course. This study, aimed at deciphering the complexities of what makes us the same and different from one another, is extremely relevant for my students who come from 30 countries and speak multiple languages. The subject also corresponds to my commitment as a teacher to develop students’ analysis of history, oppression, power, and social justice to help equip them with the tools necessary to transform themselves and their communities.

In addition to being a social studies teacher, I am also a full-spectrum doula who is trained in providing nonjudgmental support to pregnant people in all decisions and phases of their journey. I became trained in this role after watching a documentary and doing my own research on the experiences of women giving birth at hospitals. It is unacceptable that the U.S. has a steadily increasing maternal mortality rate, which is also the highest in the developed world. There is a clear need for more attention to the issue and community-based solutions, and I used my Fund for Teachers grant to accomplish both.

For one month in 2019, I conducted mini-ethnographic research on the experiences of doulas and other birth workers in New Delhi, India, to understand what challenges and opportunities they see in lowering maternal mortality rates. I chose India partly because it holds significance to me as my birthplace and because the maternal mortality rate has decreased by 22% in the country from 2011 to 2016 according to recent data. I met with individuals in hospitals and nonprofits such as Birth India to collect data through a mixed-methods approach, using both participant observation and interviews, which are two popular methods in cultural anthropology.

-

-

Neha (back, center) meeting with doulas to conversations about what it means to be a doula and what issues persist affecting pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

-

-

Supporting a women’s walk at night to be in solidarity against the ways in which sexism limits women’s ability to live freely on their own terms.

-

-

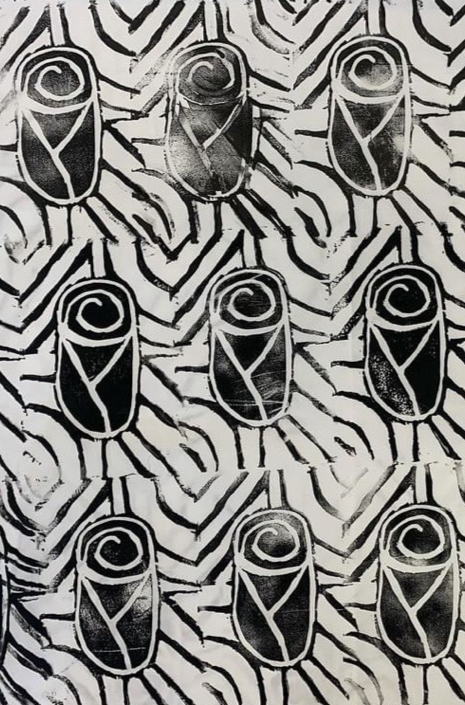

Taking notes after observing a client meeting where her birth plan and hopes/fears were discussed.

Conducting this fieldwork gathering and analyzing data equipped me with new primary resources that now model and support my students’ research inquiries for their IB Anthropology projects. And, undertaking fieldwork helped me become a better teacher because I intimately understand the challenges and excitement that comes with “doing anthropology.” Now that I did the work I ask of my students, I can better explain the process of collecting data and articulating analysis about social phenomena.

Students benefit tremendously when their teachers are given the time to become energized and gain new ideas and perspectives. Teachers who have been invested in, invest in their students in return! The type of learning Fund for Teachers affords allows us to engage in creative experiences that enhance our connections with ourselves and our subject areas. It is also great role-modeling for students to see that teachers are lifelong learners and continue to have passions and goals. As a result of my fellowship, I am now waiting to hear about my acceptance in a PhD program in Cultural Anthropology!

While my fellowship helps me most readily with my 11th and 12th grade IB Anthropology students, with whom I piloted a new Medical Anthropology unit introducing the subfield focused on the impact of social, cultural, and historical forces on health and illness, how illness is experienced by various communities, prevention measures, and the process of healing. However, my experiences in India also benefit my 10th grade students in my U.S. Government class, as well as my Latin American Studies elective course. In my government class we have a unit on domestic policy where I implemented a research project that allows students to pick an issue, such as maternal health, and propose a policy-based solution. Our high school also hosts a medical careers program, which trains a sizable amount of our student population to explore careers in the healthcare industry and my students now present their new learning about birth, public health, and combating maternal mortality to students in the medical careers program.

Learning about issues women face in India regarding birth and realizing how similar those are to what we see in America made me even more confident in creating a unit on maternal health justice. At some point in their lives, it is very likely that students will either know someone pregnant, be the person giving birth, and/or be the partner of someone giving birth. Being in any of these three positions warrants the knowledge of pregnancy and birth as one way to tackle the crisis of maternal mortality in the United States (as well as many other countries). This fellowship is leading to learning outcomes that:

- Help students understand a specific situation (maternal health and birth) both in a global context and in their country of residence and

- Teach the practice of using research to solve real-world problems.

By directing my Fund for Teachers grant to confronting the problem of maternal mortality, I’m positioning my students as the solutionaries of the present and future.

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with La Union del Pueblo Entero, a grassroots immigrant justice organization at the Texas-Mexico border, where she supported organizing efforts to fight for neighborhood development, immigration reform legislation, and workers’ rights.

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with La Union del Pueblo Entero, a grassroots immigrant justice organization at the Texas-Mexico border, where she supported organizing efforts to fight for neighborhood development, immigration reform legislation, and workers’ rights.

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with