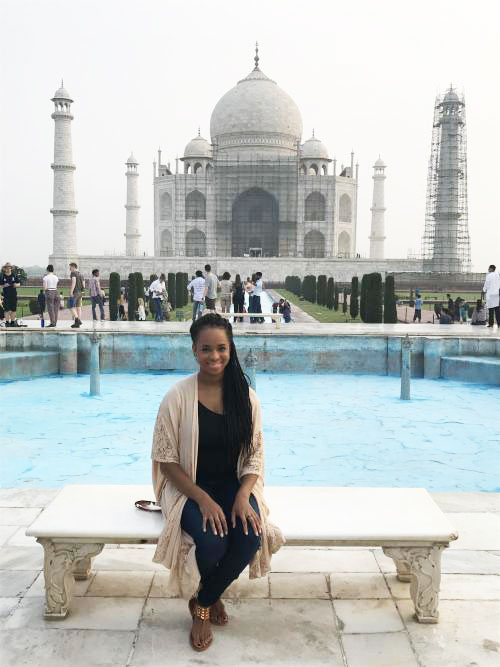

Fund for Teachers grant recipients regularly head to the Florida Keys to research marine biology and conservation; therefore, we wanted to get their insight into Hurricane Irma’s devastation. We are grateful to Lucila Telesco (Newfield Elementary School – Stamford, CT) who, in the midst of Open House – for which she was organizing translators and buses – shared her story…

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”30px 0px 30px 0px”]

I embarked on my fellowship to Florida’s Everglades and the Key’s Coral Reef during the peak of summer vacation, which happened to coincide with Florida’s wet season. Though I, a fair-skinned northeasterner, had mentally prepared myself to contend with the Florida’s notorious heat and humidity, I didn’t fully understand how unpredictable the wet season could be.

The first stop on my journey was the Everglades, a place I had always pictured as an expansive swampy grassland teeming with scaly alligators. While partly true, I came to see that the Everglades are so much more than that. On my first Everglade adventure, a boat assisted kayak eco-tour of Ten Thousand Islands, the Everglades revealed itself to be a proliferation of magical salt dwelling mangrove trees extending endlessly into the Gulf. My savvy naturalist guide navigated our small boat through the labyrinth of mangroves in Chokoloskee Bay, while explaining the area’s wonders. I learned that the Everglades are home to the one of the largest mangrove ecosystems in the world and the Ten Thousand Islands are comprised of three types of mangroves: red, white, and black; red being most prevalent. As our boat inched closer to a cluster of densely packed mangroves, I got my first glimpse of the red mangroves’ prop root system. The network of overlapping roots seemed to jut out of the water like clumsy acrobats on stilts. As we glided along, my eyes were drawn to the hundreds of seedpods, called propagules, dangling from the branches. I learned that propagules are buoyant and can stay afloat for over a year before they taking root, how incredible it that? Those hardy mangroves were captivating. They had found a way to thrive in the most inhospitable of places.

During my excursion, we anchored in an inlet to explore a sandbar connecting Lumbar and Rabbit Key by kayak. But, no less than 50 yards out the weather turned. Pavilion Key in the distance, which had been visible just minutes before, was enveloped by a dark grey fog. Before I knew it, we were caught in a deluge. My guide, fearful that lighting and thunder might follow the rainstorm, quickly led the way back to the boat. As if on cue, the moment we ambled into boat the sky dried up and returned to its stately shade of blue. It was baffling to see a storm build and subside that quickly. My guide pointed out some large fluffy clouds on opposite ends of the sky and began explaining that though they looked harmless, they had the potential to merge into a serious thunderstorm. Luckily the skies remained clear for the rest of the afternoon, allowing me to explore the sandbar thoroughly. I examined conch and lightning shells up close, and I even learned how to identify sea turtles tracks in the sand to locate their nest. By the end of my time in the Everglades, I had caught glimpses of blue herons, snowy egrets, white ibis’, ospreys, a hungry pair of dolphins, and the fleeting muzzle of a shy manatee, all of which was quite remarkable.

The next stop on my journey was Marathon Key to learn about dolphin and sea turtle conservation. I was set to drive down to Marathon when Tropical Storm Emily made landfall. But, I had places to go and dolphins and sea turtles to see, so I cautiously made my way to Marathon that day. The drive was slow and the rain was relentless, but I arrived safely and in time to see the amazing work being done at Dolphin Connection. As part of the dolphin smart wild dolphin conservation program, they rescue dolphins that have been kept in captivity and can no longer hunt, providing them with food, shelter, and training.Similarly, the Sea Turtle Hospital works to rescue, rehab, and whenever possible release sea turtles back into the wild. They have helped hundreds of sea turtles return to the wild, but the ones whose injuries are too severe to successfully survive in the wild become permanent residents of the hospital. I learned of one such injury that has been endearingly termed bubble butt syndrome. In these cases, the turtles’ shells are damaged by boat impacts, causing them to develop air pockets that render them permanently buoyant, which is a problematic state for a sea turtle that must dive for food. Researchers have attempted weighing down the shells, but since sea turtles shed the scales on their shells periodically, weights are not a permanent solution. Until we can learn to co-exist safely together, I am thankful for organizations like this that are working to protect these animals and their unique habitats.

The final stop on my journey was the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, home to the third largest barrier reef in the world. The chance to snorkel in the blue waters off the coast of Key West [pictured above] and see the vibrant array of coral and fish dancing beneath the surface of the water was unforgettable. It was like a whole little universe onto itself, unawares of the goings on in the terrestrial world. The coral ebbed and flowed as if it has never been rushed a day in its life and a school of vibrant blue fish assembled and dispersed with the agility of Olympians. I learned that the corals iridescent quality is a result of bioluminescence, a chemical reaction that releases light, which many fish also possess. Bioluminescence, much like a school of fish, is employed to appear more threatening and ward off predators. Some corals can even release luminescent particles with toxins when touched. Luckily, my guide thoroughly warned me not to touch anything before the snorkel, so I didn’t get to experience the luminescent toxin. But, the sights I did get to experience were incredible.

Another highlight of Key West was the Butterfly and Nature Conservatory. While there I overheard a little boy’s reaction, which I feel sums up the experience best. He said, “Mommy, I feel like I’m in a Disney movie and I don’t want to leave,” which is how I felt too at the end of my visit. Blue monarch butterflies fluttered about in groups and stopped momentarily to feed on honey and fruits, while bright pink flamingos bobbed in a shallow stream. A turaco, with a bright green crest on the top of it head that resembled a mohawk, was perched in a tree making a ruckus. Even though I was in a glass enclosed climate controlled conservatory, it felt like the middle of a magical forest, capable of producing Snow White and the seven dwarfs around the next bend. Key West is one of the most vibrant and colorful places I have ever visited, and turned out to be the perfect culmination to an extraordinary fellowship.

So, it is with a heavy heart that I learned the Keys and South West Florida were among the most devastated by Hurricane Irma. I want to remember it as it was, thriving, chock full of passionate people dedicating their lives to protecting and restoring it. In aftermath of the hurricane, I was relieved to hear stories of hope from the many remarkable people and places I visited. I learned my Everglades guide is safe and unfazed by the blackout. The staff and dolphins of Dolphin Connection in Marathon Key were safely evacuated to facility in Orlando prior to Irma and are glad to report their dolphin lagoon survived the worst of the hurricane. The Sea Turtle Hospital is operational. Its staff and recuperating turtles also weathered the storm successfully, and they are already admitting new patients. As if by miracle, the glass enclosed Butterfly and Nature Conservatory in Key West was untouched by Irma. If I learned anything on my fellowship it is this: plants and animals possess an incredible ability to adapt to their environments. Hurricane Irma showed me that people do, too. They were all tested, but remain, and like the resolute mangroves are determined to thrive in the most inhospitable of places.

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”30px 0px 30px 0px”]

Lucila is an ESL teacher with a passion for conservation. In addition to Masters degrees in TESOL and Reading Instruction, her accomplishments include: Presidential Arts Scholar and member of the Arts and Cultural Cohort of the Women’s Leadership Program at George Washington University. In the future, she hopes to combine her love of nature, storytelling and languages to pen a multicultural children’s book.