The conservation of France’s Camargue wetlands represents the opposite of rags to riches: It’s millionaire to marshlands manager. In 1948, a young heir to the Roche pharmaceutical fortune spent a bit of it to buy an estate in a mosquito-infested, briny marshland. The region also was the second-largest delta draining into the Mediterranean Sea, behind the Nile. Twenty-five-year-old Luc Hoffmann saw the value in preserving the Camargue. And seventy-five years later, FFT Fellow Frederic Allamel saw the value in teaching about it.

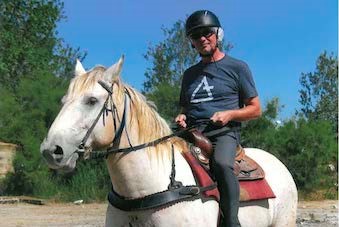

“I designed this fellowship to allow learners to better grasp the fate of coastal communities facing ocean-level rise and their attempt to preserve their cultural identity in the context of climate change,” Frederic explained. “Furthermore, the aim of this inclusive approach is to generate empathy towards ethnic minorities striving to preserve their cultural heritage, including nomadic Gypsies and the iconic gardian (the cowboy of the marshes).”

The Fellowship

For seven weeks, Frederic conducted research from the Provencal town of Arles to accomplish three goals:

- Establish a glossary of the most prominent markers (i.e., ’Provençal’ dialect, vernacular architecture, symbolic bestiary) along with their significance in ‘Camarguaise’ culture.

- Focus on the articulation of these markers and the fabric of a unique blend of cultures — ‘gardians’, ‘gitans’ (Gypsies), ‘cueilleurs de sel’ (salt gatherers), etc. — through the recording of life histories.

- Develop a partnership between my students and their peers in Camargue through the creation of visual archives mapping distinctive landscapes and human activities in this threatened region, as well as strategies to cope with climate change.

“Besides the beauty of its landscape (pink marshes surrounded by white salt domes), I experienced firsthand the harshness of this lifestyle, working under the sun in extreme heat and being blinded by the whiteness of the salt,” he said. “It was a challenging body experience, although the camaraderie felt alongside other workers helped me gain their unique sense of place.”

- The Camargue is known all over Europe for its biodiversity and iconic pink flamingos.

- Being introduced to the Camargue via thelifestyle of the ‘wetland cowboys.’

The “Followship”

Now, his students at the International School of Indiana are engaged in a new Global Politics class using data and images Frederic collected on his fellowship. Supporting students’ acquisition of an International Baccalaureate (IB) diploma, they are working toward projects addressing climate change and societal implications. Additionally, an intrinsic aspect of the IB diploma is a service, which Frederic intends to inject through student involvement with local organizations involved in environmental justice work.

“This fellowship reinforced in my belief that gaining firsthand knowledge is a prerequisite for being an engaged educator whose communication skills rely on experiential-based expertise that aim to be inspirational for students,” Frederic said.

Frederic is a two-time FFT Fellow. In 2017, he designed a fellowship to study Aboriginal arts in central/northern Australia with a focus on environmental symbolism to provide a case study for Anthropology of the Environment students.

“I collected numerous artifacts from the Shipibo Indian tribe with the intention of initiating a long-term class project. Consequently, my students became key actors of the Anthropology Club, whose goal was to design a bilingual catalog (English/Spanish) and curate a show that was eventually on display at Indiana University in Bloomington for a whole year. This project allowed students to develop a strong team spirit while applying a vast array of skills (translation, research, photography, logistics, etc.) to in the end deliver a near-professional publication and exhibition.”

Access that exhibit here.

(Top photo courtesy of the MAVA Foundation for Nature.)