This month, 230 prek-12 teachers are learning around the world with Fund for Teachers grants, making this our busiest “Fellow Season.” Highlighting one teacher for our weekly Friday Fellow post is tough, as our exemplary grant recipients are checking in from near and far with updates that inspire wanderlust from behind our computers. In light of this holiday weekend, however, Jean Molloy‘s learning seems most timely.

Jean teaches American History at Robbins Middle School in Farmington, CT. She is currently in the middle of her fellowship exploring Civil War landmarks, monuments, and museums in four southern states to document how historians preserve and honor the past while maintaining values respectful to all Americans. We caught up with Jean to see how the research is going…

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Why this fellowship? Why now?

As a U.S. history teacher, I need to develop the critical thinking and reasoning skills of my 8th graders. Students tend to accept non-fiction text without questioning or extending their thinking and they struggle when reading primary sources. Middle school students sometimes have difficulty understanding the perspectives of others. One of the social studies standards that we want them to master in my district is the ability to analyze both primary and secondary sources to determine claims, evidence, and perspective. One of my goals is to help them improve this skill which is imperative to creating lifelong learners as students navigate through controversial issues throughout their education and beyond.

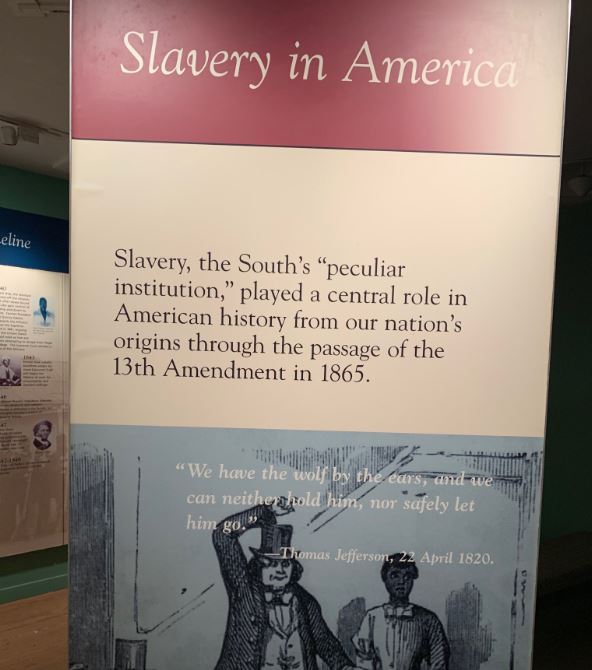

- The American Slavery exhibit at the Museum of the Civil War Soldier

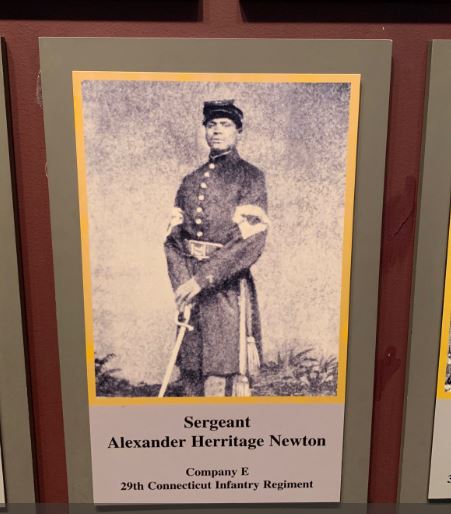

- An interactive experience features Alexander Newton from Connecticut 29th Colored Regiment during the Siege of Petersburg

My fellowship will help me frame the following key questions for my U.S. History course:

- How should Americans preserve history and at the same time be respectful to all humanity?

- How do decisions about preserving our past impact how we live today? And,

- What actions can we as citizens of a democracy take to make sure we preserve our history and learn from the past?

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

What’s on the itinerary?

A great focus of the fellowship is on National Parks where significant events took place, but I’m also visiting some state- and privately-funded museums and engaging in conversations with curators, docents, and volunteers to help in my evaluation of how Americans are preserving our history. In Gettysburg, I’m participating in two professional workshops for teachers: What was the Civil War really about? and Why do we preserve and protect Battlefields? In Richmond, I plan to meet with a member of the City Historic Preservation Committee to discuss the five Confederate statues on Monument Avenue. I hope to secure an interview with representatives of a movement to remove the statues as well. According to a survey conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2017, “…our schools are failing to teach the hard history of African enslavement.” I chose destinations that will inform my teaching of this history in a balanced and coherent manner and also help students see the connections between our past and our society today.

Have you experienced any “A Ha!” moments you particularly want to share with students?

I am about half-way through my Civil War exploration and it is hard to process all that I have learned so far! Speaking with park rangers, museum docents and volunteers has deepened my understanding of this great conflict in American history and especially of the key people who were making critical decisions on each side. I have also learned that Virginians are very proud of their history and they want to talk about it. In addition to interacting with professional historians, I have been speaking with people in restaurants, B&Bs, and with other tourists at historical locations. I would have walked right by a slave auction block on a Fredericksburg street corner if I had not been chatting with my waitress at dinner. She explained how the city council recently voted to remove the block to a museum. I had to stop and think about what it must be like to walk by this every day which prompted me to dig a little deeper. The Fredericksburg website states that, “It is important to recognize that the City Council decision-making process, specific to the future of the auction block, has been taking place within the larger context of a community dialogue about race, history, and memory.”

I am about half-way through my Civil War exploration and it is hard to process all that I have learned so far! Speaking with park rangers, museum docents and volunteers has deepened my understanding of this great conflict in American history and especially of the key people who were making critical decisions on each side. I have also learned that Virginians are very proud of their history and they want to talk about it. In addition to interacting with professional historians, I have been speaking with people in restaurants, B&Bs, and with other tourists at historical locations. I would have walked right by a slave auction block on a Fredericksburg street corner if I had not been chatting with my waitress at dinner. She explained how the city council recently voted to remove the block to a museum. I had to stop and think about what it must be like to walk by this every day which prompted me to dig a little deeper. The Fredericksburg website states that, “It is important to recognize that the City Council decision-making process, specific to the future of the auction block, has been taking place within the larger context of a community dialogue about race, history, and memory.”

In most of the Civil War Museums, there have been exhibits that also document the story of slavery in America, its role in the Civil War, and in American economics. Although I have grappled with how this story should be preserved, what I have seen so far in Virginia has helped me learn and is helping me frame questions for my students.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Jean teaches 8th grade U.S. History, which includes a project based learning event on local history. Previously, she taught 7th grade Asian studies and participated in a teacher exchange program with the Republic of Korea organized by the East-West Center for UNESCO and also a teacher study tour in China with the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. You can follow Jean’s FFT fellowship on Twitter @IARMolloy.

Jean teaches 8th grade U.S. History, which includes a project based learning event on local history. Previously, she taught 7th grade Asian studies and participated in a teacher exchange program with the Republic of Korea organized by the East-West Center for UNESCO and also a teacher study tour in China with the National Consortium for Teaching about Asia. You can follow Jean’s FFT fellowship on Twitter @IARMolloy.