So That Others May Learn

Last summer with a Fund for Teaches grant, Dr. Shelina Warren and four peers from Dunbar High School in Washington DC embarked on a journey across five states in the Deep South to more effectively teach complex and accurate historical narratives about race, civil rights, and the African American experience. In advance of Martin Luther King Day, we reached out to Shelina to learn more about their experiences and how students are learning differently as a result…

You saw/experienced/internalized so much history on your fellowship. Is there one moment that stands out above the others?

One of the most profound moments of the fellowship was standing inside the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, at the exact site where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life. The emotional weight of being in that space was unexpectedly similar to what I felt days later in Mississippi—standing in the courthouse where Emmett Till’s killers were acquitted and near the river where his body was found.

In both places, I felt the same question pressing in on me:

How do we teach students not only what happened, but how people responded—and what those responses demand of us today?

That question is at the heart of what I was trying to solve through writing and receiving this fellowship.

And what were you trying to solve?

Before the fellowship, my students could name incidents of racial violence—Martin Luther King, Jr., George Floyd, Breonna Taylor—but they struggled to articulate:

- How people responded in those moments;

- Why those responses mattered; and,

- What choices they themselves are inheriting today

A pre-survey I administered at the start of my Emmett Till unit confirmed this gap:

- While students expressed strong emotional reactions to racial violence, many lacked confidence in explaining historical responses beyond protests or anger.

- More than 80% of students indicated that primary sources, real locations, and personal narratives helped them understand people’s choices more than textbooks alone.

- Nearly all students said they believe their responsibility today is to speak up when we see injustice, but many were unsure how to do so meaningfully.

The fellowship helped me realize that place-based learning—standing where history happened—is essential to bridging that gap.

How is your fellowship’s place-based learning informing students in the various classes you teach?

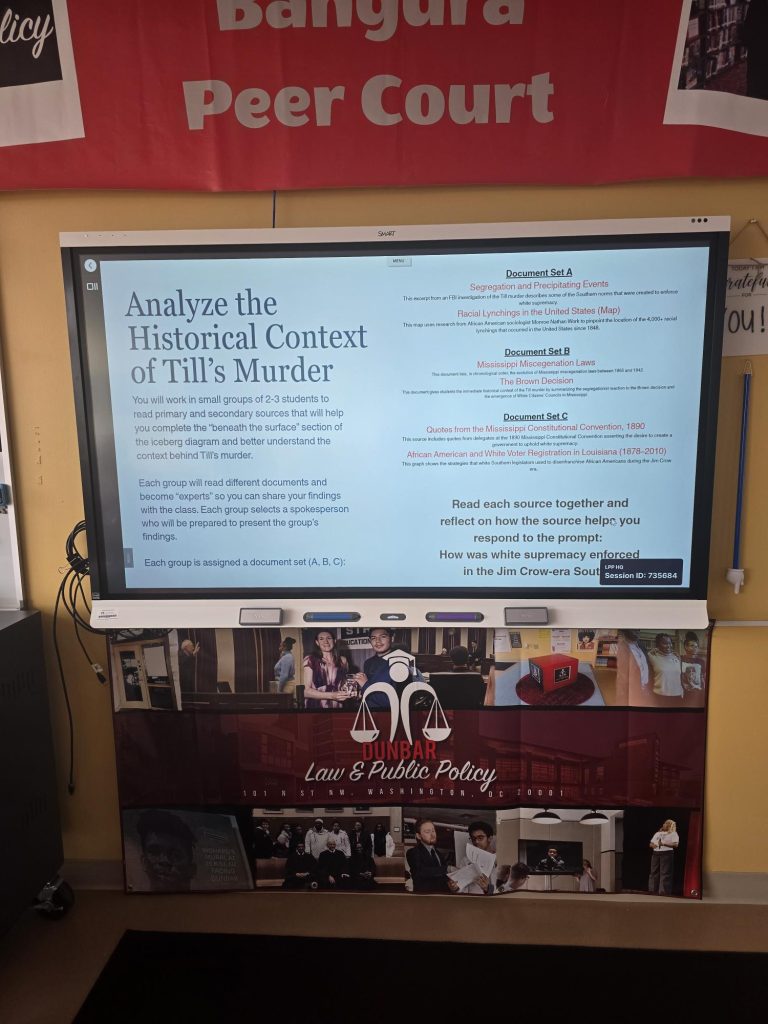

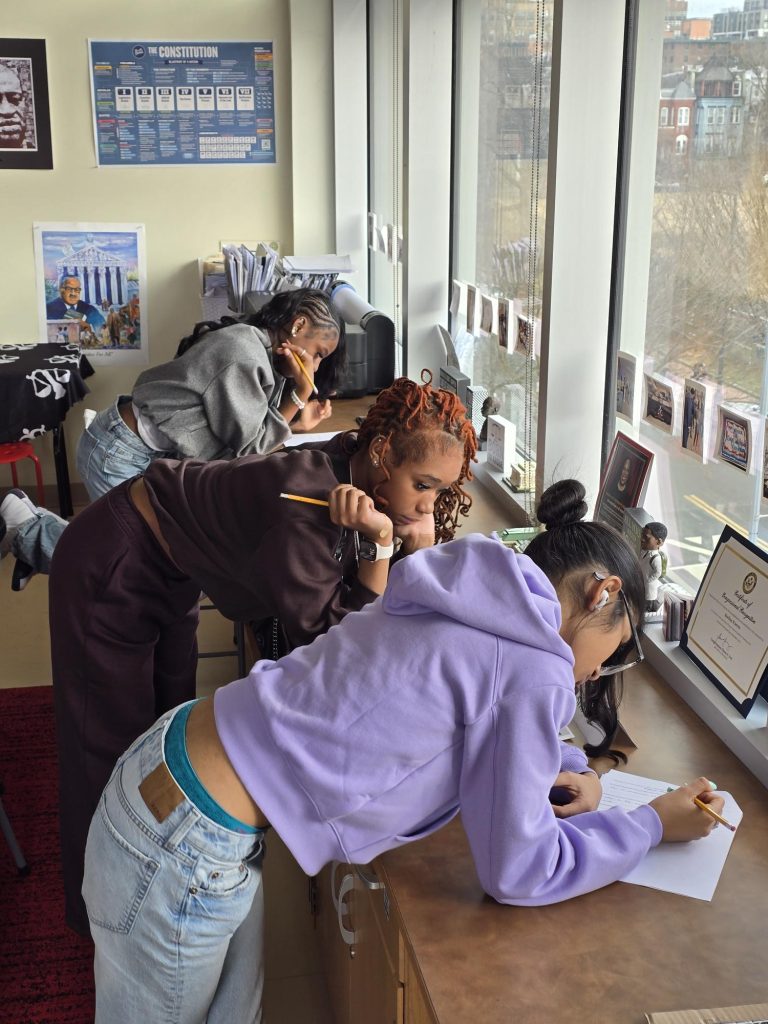

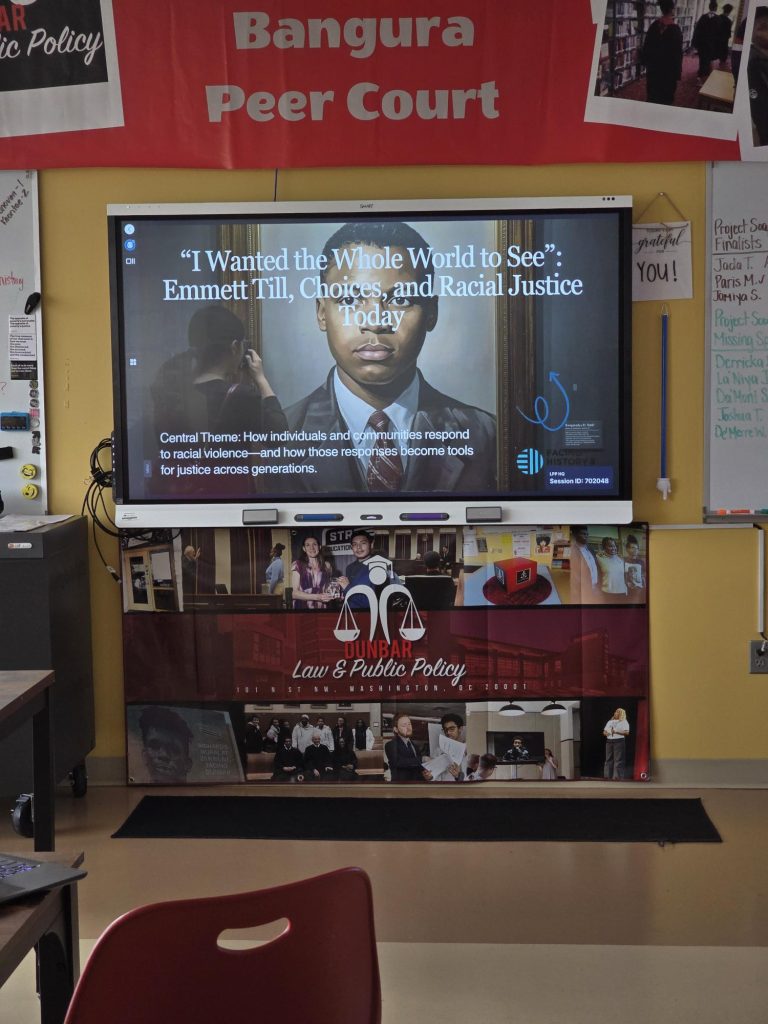

I am currently teaching a mini-unit on Emmett Till grounded directly in the fellowship experience, which specifically features high school curriculum activities and resources I received from the Emmett Till Interpretive Center and Facing History & Ourselves. Students are engaging with:

- Photos and videos I captured at the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, courthouse, barn, and river as primary sources;

- Documentary clips and insights shared by scholar Ben Saulsberry;

- Comparative inquiry connecting Emmett Till’s murder to Dr. King’s assassination and contemporary racial violence; and,

- Structured discussions centered on the essential question:

As we pursue racial justice today, what can be learned from the choices people have made in response to racial violence in the past?

“Seeing the real places where Emmett Till’s story happened made it feel real in a way textbooks never did. It made me think about what I would have done then—and what I should do now.” — Dunbar High School Law & Public Policy student

Alongside this unit, I am developing:

- A student-created video project modeled after the National Civil Rights Museum introductory film, highlighting the legacy of our Law & Public Policy Academy

- Podcast episodes that weave together fellowship sites, including an on-location sound bite recorded outside Dooky Chase’s Restaurant—a historic civil rights strategy space

- A classroom Matter of Law panel series inspired by the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, where students examine court cases and consider legal vs. moral justice

With two decades of teaching and a Ph.D. in Urban Leadership, is there anything new that you learned on this fellowship?

Visiting Dr. King’s childhood home, final resting place, and the King Center in Atlanta helped me more fully understand the arc of his life—not just his death. Seeing where he was raised, where his ideas were nurtured, and where his legacy is preserved allowed me to teach him not only as a martyr, but as a strategist, organizer, and human being.

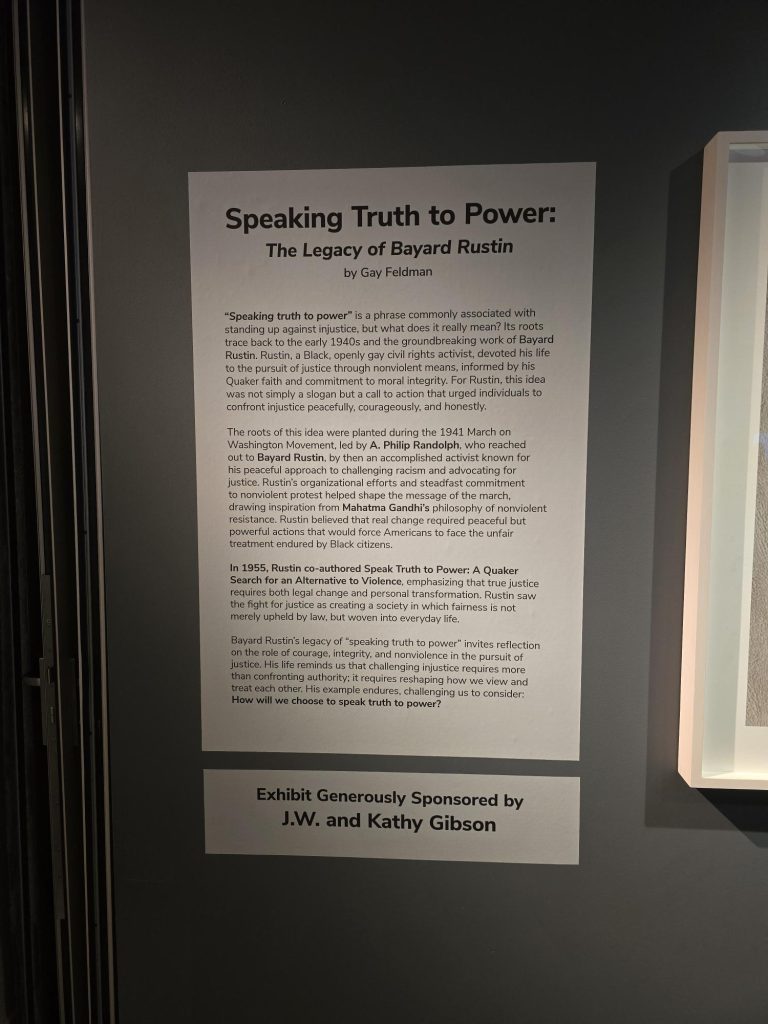

At the National Civil Rights Museum, I also learned the origins of the phrase Speaking Truth to Power through Bayard Rustin’s work. That learning reshaped how I frame activism for students—helping them see that justice requires both legal change and personal transformation.

One quote from Studio BE in New Orleans captured this tension perfectly:

“How do you look terror in the face and still muster the courage to love?”

That question now anchors my classroom. Love, I tell my students, is not passive—it is a deliberate act of resistance, one Dr. King embodied fully.

I’m extending our fellowship’s beyond my students and me through:

- Podcast episodes shared with families and the community

- Ongoing conversations with colleagues about replicating place-based learning locally

- An upcoming Humanities Circle presentation where I will share my Emmett Till unit and fellowship-based strategies

The recent CBS Sunday Morning update about preserving the Emmett Till barn—and Shonda Rhimes’ continued support—only reaffirmed why access to these sites matters. Memory is fragile. Place helps protect it.

At the heart of this fellowship is the belief that guides my work: So that others may learn. This experience strengthened my commitment to teaching truthfully, lovingly, and courageously, and to helping students understand that their responses to injustice matter.

Dr. Shelina Warren is the Law and Public Policy Academy director at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Washington, DC, where she teaches multiple courses, including Constitutional Law and Youth Justice. She is an Arkansas native, Army veteran, and National Board Certified social studies teacher/leader, finishing her 22nd year in education. She has a doctorate in Urban Leadership from Johns Hopkins University, which focused on civic empowerment for African American students.

Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs