Fund for Teachers Fellows teach every subject and language, including American Sign Language (ASL). At FFT Fellow Mick Posner‘s school in West Hartford, CT, ASL is one of the world languages offered and he used his grant to learn from deaf Inuits in Nuuk, Greenland, basic conversational skills in that country’s official sign language system to expand current ASL classes and deepen students’ understanding of the human spirit’s resiliency.

Fund for Teachers Fellows teach every subject and language, including American Sign Language (ASL). At FFT Fellow Mick Posner‘s school in West Hartford, CT, ASL is one of the world languages offered and he used his grant to learn from deaf Inuits in Nuuk, Greenland, basic conversational skills in that country’s official sign language system to expand current ASL classes and deepen students’ understanding of the human spirit’s resiliency.

FFT Fellows Amanda Kline and Jenny Cooper‘s situation is a little different. They are teachers of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing at Metro Deaf School in Sant Paul, MN. Metro Deaf School is a pK-12, free public charter school that provides bilingual and interdisciplinary curriculum using ASL and English for students who are primarily Deaf, DeafBlind, and Hard-of-Hearing. Enhancing their curriculum are short, timely lessons they create for their YouTube series Did You Know That?!

Amanda (who produces the videos) and Jenny (the host and who is deaf) created a Fund for Teachers 2020 fellowship to document pedagogies of Deaf cultures and communities across Iceland, Scotland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Ireland to provide linguistically-accessible primary resources that increase world knowledge for and decrease language gaps of deaf students. Due to COVID, they had to defer their fellowship, but we wanted to touch base now to learn more about their plans through a Q&A interview…

The YouTube segment “Inaugural Poet Amanda Gorman’s Speech & Auditory Processing Disorders”

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]In your proposal, you wrote: “Many of our students have grown up with world experiences; but without the language to accompany those experiences, they are unable to process, understand, internalize, or apply their experiences.” When your students experience everything, yet rarely have the language for processing and sharing, how do you build community?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]There is community building in the simple “same as me” experience among students. Empathy is a deep thread that runs throughout our student body DNA. When students transfer to our school at 12 years old having had 12 years of life experience with 0 years of language and are finally given access to ASL to process those experiences, we see so much growth. Then, when other students transfer in after them, those students can come alongside them to support growth. It is also important for them to see how far they’ve come! Taking language sample videos and then showing them those videos 1-2 years later is always a treat!

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]You have 12-year-old in your classes, deaf, 12 years old, and at a 3 year old math and 0 year old reading level, yet within less than two years, you have that student perform at a 5th grade math level and reading at a 3rd grade level. How do you motivate and inspire students with such obstacles to achieve at these levels?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]Honestly, they don’t need extrinsic motivation, it’s an innate need, passion and desire. When they can understand what’s happening, their cognition goes into hyper-speed.

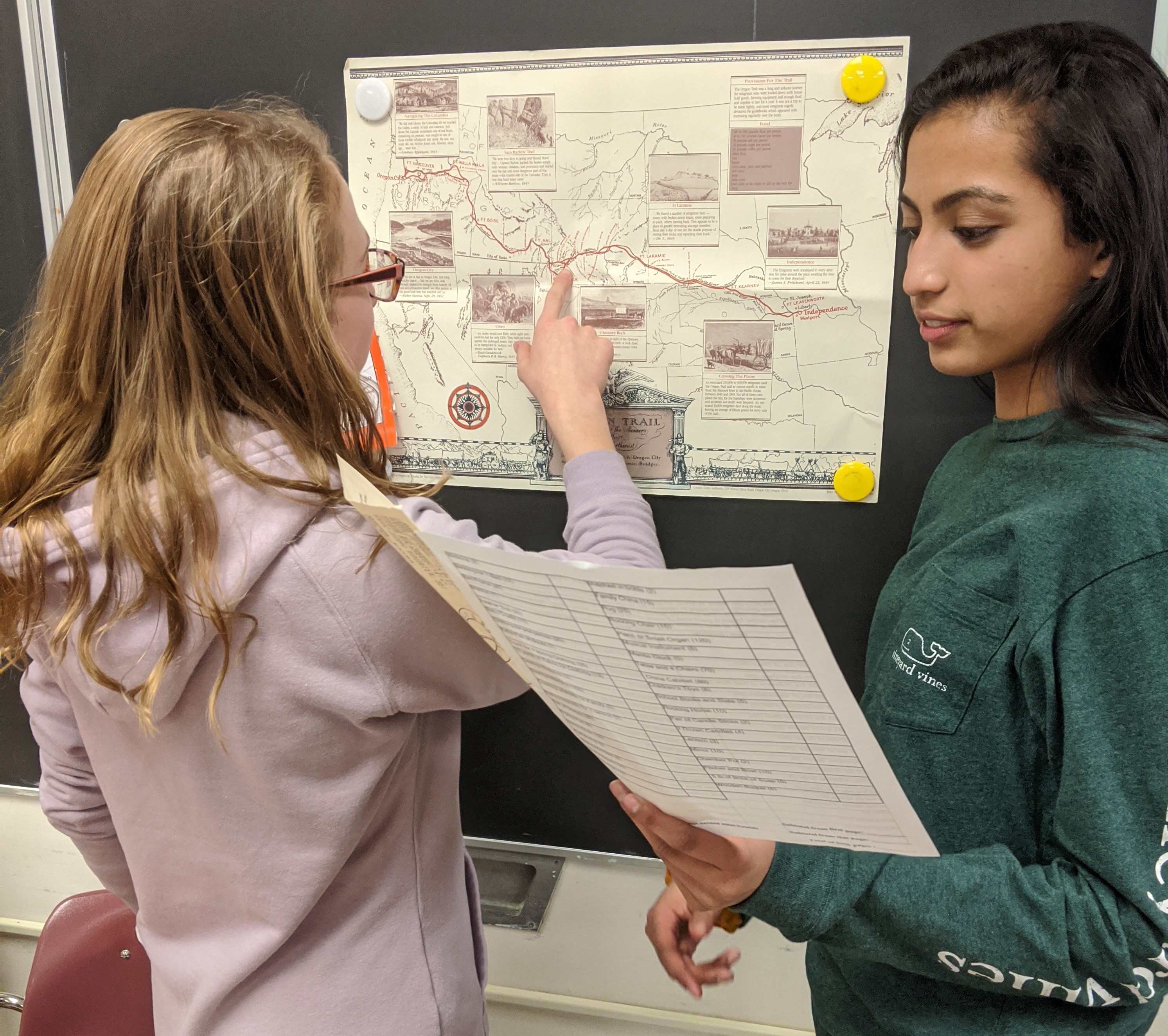

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]While your fellowship involves filming historically-significant sites, you also plan to focus on significant elements of the respective deaf communities such as: traditional folklore, celebrations, and language evolution. Can you talk more about that?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]Yes! We are excited to be visiting various Deaf Clubs, Deaf community gatherings, Deaf immigrant immersion programs, and much more. We can’t wait to see how these various cultures incorporate their local cultures and history overlap with Deaf culture and history. For example, by meeting with the Scottish Ethnic Minority Deaf Club, we will experience how members celebrate various diverse people groups within the Deaf community and take away ideas for events, programs, and approaches to be able to apply within our own community.

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]Your research will also include interviewing organizations about building community with parents. Why do you feel as though that is vital?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]Students can grow and learn 8 hours a day when they’re with us, but when they go home in the evenings, weekends, and during school breaks, that’s where they need continued education and support in ASL. When families get on board with their child’s newly acquired language, we see significant growth in those students.

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]Would you explain the SignPal program and your plans for implementing it with your students?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]We piloted a program like this within our own state a few years ago where we networked with another deaf school. This operated similarly to traditional Pen Pals, but in ASL using sign as opposed to writing in English only. We paired up students based on language levels, then they sent videos back and forth to one another, getting to know another person. We provided guided questions for suggestions. At the end of the academic year, we all met together at a local Deaf club where we had a tour and lesson about the history of the Deaf club, then had lunch together and played games. This proved to be a rich social experience for all students involved and formed lifelong connections. We would like to try a program like that, but to make it an international experience.

[minti_dropcap style=”box”]Q[/minti_dropcap]Lastly, how do you foresee your fellowship impacting the Metro School for the Deaf school community?

[minti_dropcap style=”circle”]A[/minti_dropcap]We, as a team, as a school, and as a community, recognize American deaf culture is complicated and we recognize the ways the education system is failing our D/HH students; however, we also recognize our students are full of passion and drive. They need a global deaf identity, including more creatively-designed, visually-engaging, linguistically-accessible resources to be successful in their futures in the global society and marketplace. This experience will lead to opportunities for our students, staff, and community members to analyze their current cultural and educational situations and to problem solve with the support of an expanded global-knowledge. This is not a change that can happen overnight, it requires a community and a culture of first becoming aware of options, then being willing to adapt and change for the future benefit of each individual. Thankfully, the deaf community is a profoundly adaptive group of individuals willing to grow.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Jenny Cooper (right) teaches American Sign Language and more to deaf/hard of hearing high school students at Metro Deaf School. Her passion comes from her family who are also deaf, making her a third generation deaf person in her family. She obtained her Masters from the only deaf university in the world, Gallaudet University. Amanda Kline teaches deaf and hard of hearing middle school students reading and language arts at Metro Deaf School. She is passionate about making learning exciting, impactful, and memorable. She enjoys combining world knowledge with creative film making and editing to create accessible videos for ASL users throughout the country and world.

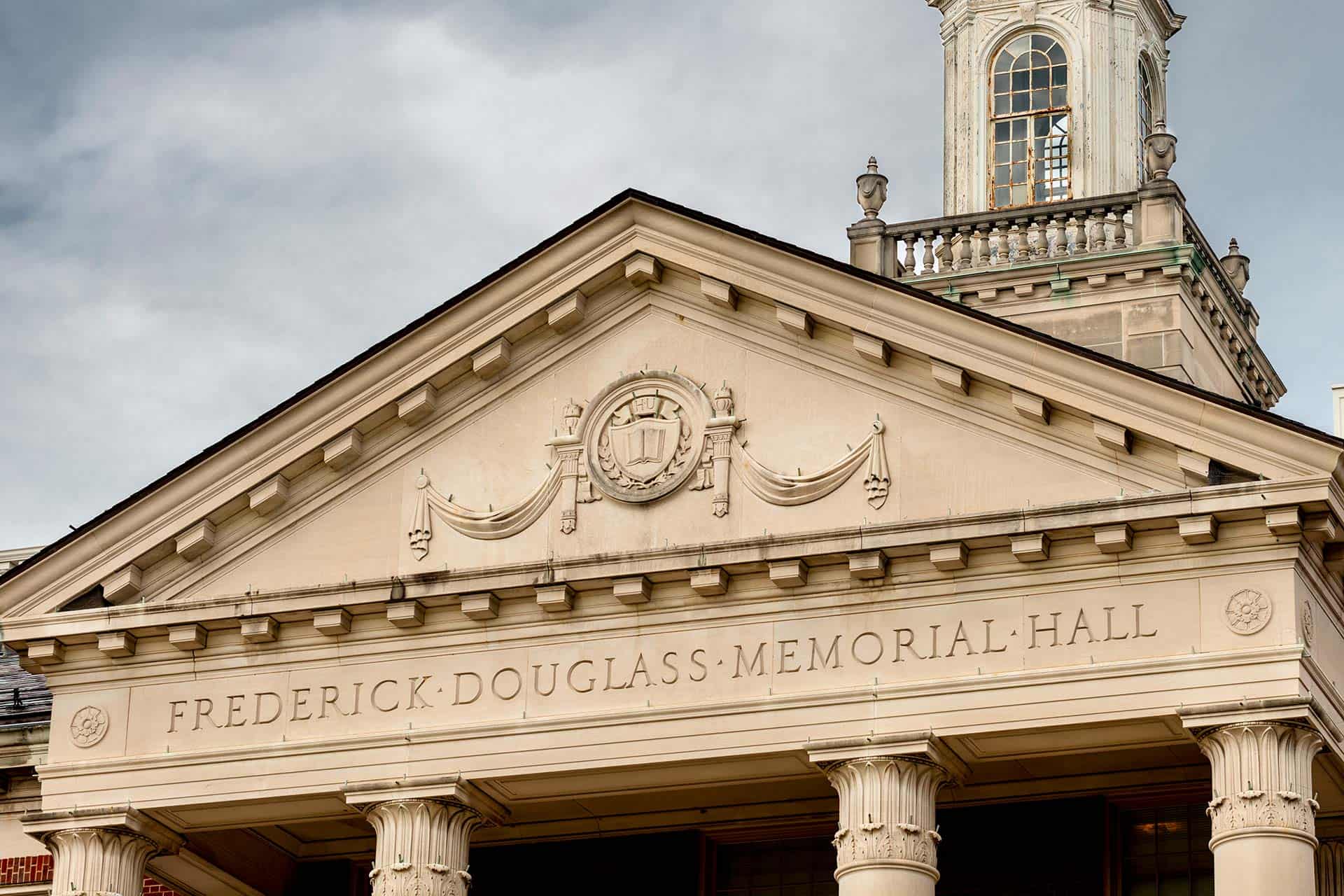

Today, millions of people received a “Breaking News” alert from The New York Times with the heading: “Over 500 Native American children died at U.S. schools where they were forced to live between 1819 and 1969, an initial federal inquiry found.” This is old news to FFT Fellow John Goodwin, who teaches U.S. History, Native American History, and an interdisciplinary research and writing course at BASIS Phoenix. In March, his book Without Destroying Ourselves: A Century of Native Intellectual Activism for Higher Education was released and this summer he will further his research to increase students’ exposure to diverse primary history sources.

Today, millions of people received a “Breaking News” alert from The New York Times with the heading: “Over 500 Native American children died at U.S. schools where they were forced to live between 1819 and 1969, an initial federal inquiry found.” This is old news to FFT Fellow John Goodwin, who teaches U.S. History, Native American History, and an interdisciplinary research and writing course at BASIS Phoenix. In March, his book Without Destroying Ourselves: A Century of Native Intellectual Activism for Higher Education was released and this summer he will further his research to increase students’ exposure to diverse primary history sources. The first phase of John’s fellowship will include documenting content and artifacts at the NMAI and taking advantage of the archival databases at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, MD and the National Archives. Afterwards, he will conduct additional research at Phoenix’s Heard Museum before heading to Fort Lewis College in nearby Durango, CO — a four-year college that once served as an American Indian boarding school.

The first phase of John’s fellowship will include documenting content and artifacts at the NMAI and taking advantage of the archival databases at the NMAI Cultural Resource Center in Suitland, MD and the National Archives. Afterwards, he will conduct additional research at Phoenix’s Heard Museum before heading to Fort Lewis College in nearby Durango, CO — a four-year college that once served as an American Indian boarding school.

Amanda Hope is a K-5th grade Gifted/Talented Program teacher at Nancy Moseley Elementary in Dallas, Texas. Amanda has served as a classroom teacher for nearly 10 years. She most recently received the 2020-2021 Campus Teacher of the Year award at her school. In addition to teaching, Amanda is a senior policy fellow with

Amanda Hope is a K-5th grade Gifted/Talented Program teacher at Nancy Moseley Elementary in Dallas, Texas. Amanda has served as a classroom teacher for nearly 10 years. She most recently received the 2020-2021 Campus Teacher of the Year award at her school. In addition to teaching, Amanda is a senior policy fellow with

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

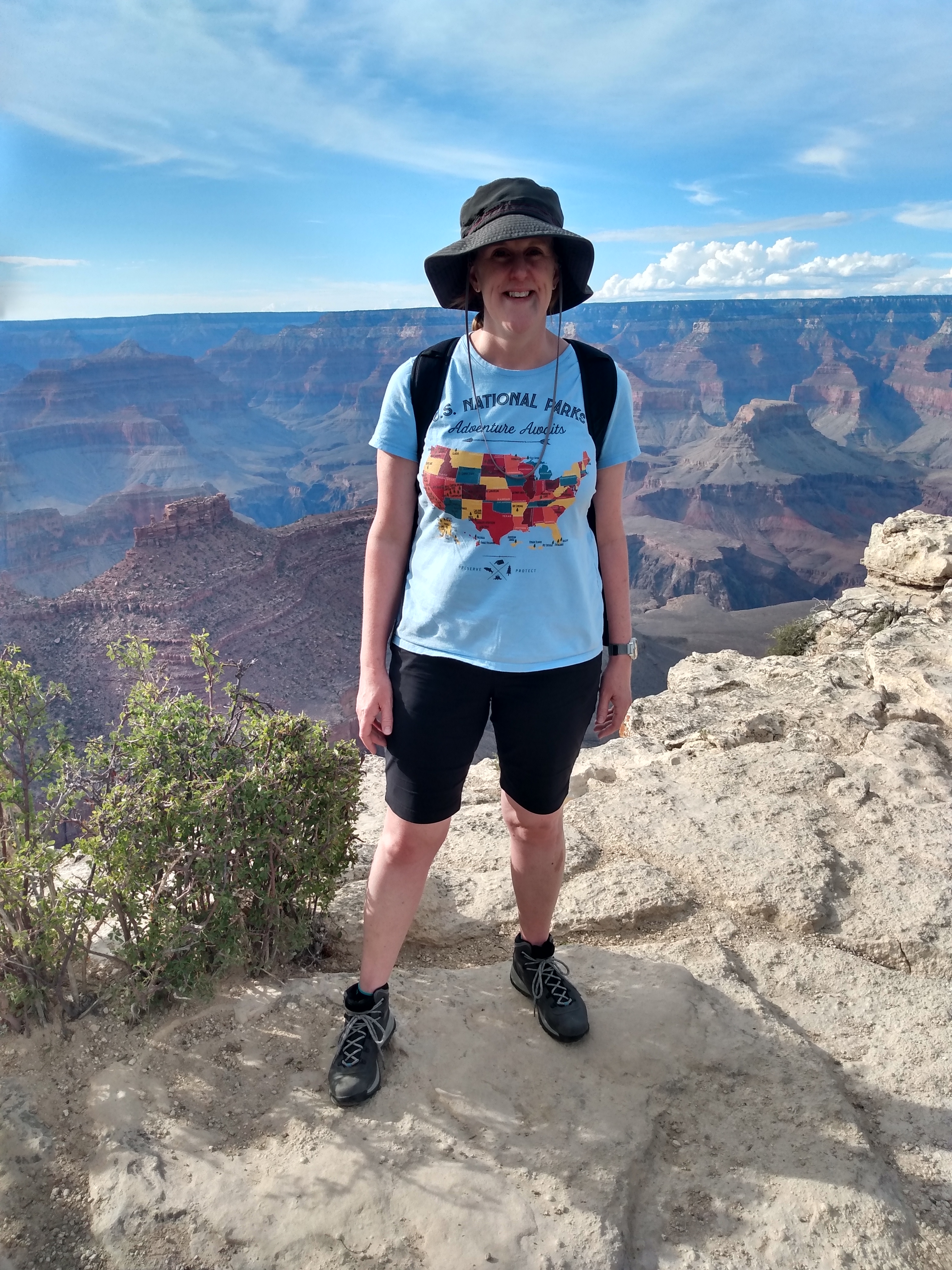

Julie McGowan (Albertville, AL) chose the Grand Canyon as her fellowship destination to show students the relationship between land and water. Her tour included a float down the Colorado River with a guide who incorporated her Navajo Indian heritage into the learning. Her experiences not only enhance new “Land and Water” unit that aligns with the Alabama Course of Study Science Standards, but also enriches teachers she trains as part of the

Julie McGowan (Albertville, AL) chose the Grand Canyon as her fellowship destination to show students the relationship between land and water. Her tour included a float down the Colorado River with a guide who incorporated her Navajo Indian heritage into the learning. Her experiences not only enhance new “Land and Water” unit that aligns with the Alabama Course of Study Science Standards, but also enriches teachers she trains as part of the