This is the final in a four-part series in which we consider what innovation in the classroom will look like going forward. Thank you to today’s contributor, FFT Fellow Liza Eaton. Liza is also our director of Ramsden Project programming.

Liza on her fellowship biking across Europe investigating renewable energy and alternative energy sources and technology.

In 2017, Fund for Teachers began to envision a new chapter for itself — doubling down on its commitment to teachers’ professional learning by asking the questions:

What if, in addition to self-designed fellowships, we engaged teachers in the design of additional opportunities to identify, address and solve problems of practice in partnership with other Fellows?

What if Fund for Teachers were to create programs with teachers, instead of just for them?

This move would take self-designed professional learning to a whole new level: for teachers by teachers.

Typically, programs are designed by contractors who observe classrooms to identify needs and dream up new (and sometimes crazy) ideas to implement in schools. Notable programs have been designed this way, like Khan Academy flipped classrooms, or IDEO’s lunch redesign. What rarely happens, however, is that designers sit alongside users to design programs. This approach takes teachers out of the design process. Instead, they are expected to use ready-made curriculum, fit into ready-made schedules and implement ready-made assessments — neglecting important teacher insights.

However, with Fund for Teachers grants, teachers have stepped up to the plate and created their own, self-designed professional learning experiences for the past twenty years. Time and time again, teachers share how this experience re-charged their batteries and elevated their professionalism. Beyond that, the relevant and purposeful learning experiences that teachers were inspired to create have increased engagement and ownership in classrooms across the country.

In 2020 we began to expand our programming beyond the summer fellowship, sitting alongside Fellows to do so. Of course, we used surveys, focus groups and interviews to understand our Fellows’ most pressing needs. But beyond that, we engaged a consistent Fellow Design Team to partner with us to glean insights and opportunities. Following the Design Thinking process, we dreamt up solutions to teachers’ needs:

- Fellows told us that they needed someone to help them navigate their learning experience and implementation, so we designed a Mentor Program.

- Fellows identified a handful of topics that they needed support with: so we tested professional learning communities. These PLCs morphed into a new grant program, Innovation Circles, based on Fellows’ needs for learning opportunities with less travel.

- Our current design challenge: How do we spark teachers’ leadership and innovation with all of the rich, first-person resources gathered on fellowships?

These programs are new so the results of our endeavors are still to be realized, but we have already identified important benefits to our approach. Partnering with Fellows helped us understand more clearly teachers’ needs and elevated our insights beyond those gathered from more traditional methods. For example, early this year, we set out to design an online platform to host Fellow-designed lesson and unit plans, only to find that that was not something that our teachers’ really needed. In addition, we have been struck by how many fellows are looking for leadership opportunities. We have been flooded with interest from our fellows – many wanting to be mentors, leaders and designers. Not only is this trend important to our program design, but it points to a real need in education: leadership pathways for teachers.

Time will tell how our programming will grow and develop, but our experience thus far has reinforced our belief in our program mindset: for teachers, by teachers.

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Liza Eaton (a 2006 FFT Fellow) is the director of Fund for Teachers’ Rasmden Project, an initiative to support and engage grant recipients beyond their initial fellowships. Her expertise lies in educational design and instructional coaching, leveraging her experience as a consultant and teacher with EL Education, Shining Hope Communities in Nairobi, and various schools in the Denver area. Liza holds an undergraduate degree in Environmental Policy & Behavior from the University of Michigan; a master’s of Curriculum and Leadership from the University of Denver; and is pursuing a doctorate in Education Equity from the University of Colorado Denver.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

Nate Moore is a math and science teacher at the Santa Fe School for the Arts & Sciences. He loves learning along with his students. For the past 11 years, he has strived to create engaging learning experiences for middle schoolers. Nate is especially proud of the River Warriors project, through which students have collected data and engaged in ecological restoration at the Santa Fe River since 2010.You can follow Nate’s teaching on

Nate Moore is a math and science teacher at the Santa Fe School for the Arts & Sciences. He loves learning along with his students. For the past 11 years, he has strived to create engaging learning experiences for middle schoolers. Nate is especially proud of the River Warriors project, through which students have collected data and engaged in ecological restoration at the Santa Fe River since 2010.You can follow Nate’s teaching on

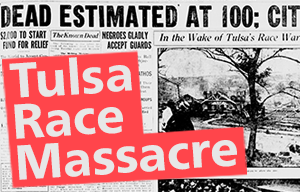

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with

Neha Singhal is a high school teacher in Maryland who has taught students in several courses: IB Anthropology, Government, U.S. History, Latin American Studies, and College/Career Prep. She has also taught various courses in Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Prior to becoming an educator, Neha worked with