Fund for Teachers encourages a holistic approach to designing a fellowship by asking teachers to consider:

- what is missing from their classrooms and school communities

- why this grant specifically will address those gaps, and

- how they and their students will benefit going forward.

For Jillian Swinford and Piotr Wojciaczyk (Pulaski International School of Chicago), COVID influenced all three answers.

“International Baccalaureate was the guiding philosophy at our school and our cohesive curriculum allowed students to apply their knowledge across all subjects for real-world learning and the transfer of their knowledge in creative and expressive ways,” wrote the teachers in their grant proposal. “Unfortunately, the pandemic forced a shift away from these principles to focus more strictly on reading and math instruction to make up for ‘learning loss.’ The negative effects of these changes can be seen in student achievement and the lack of collaboration among teachers.”

An additional COVID casualty was connections that celebrated learning, resulting in isolation from the community, their peers and even themselves. Piotr and Jillian chose to design a fellowship that would reintegrate the school’s IB focus, reunite students, and elevate a global culture within the school community undergoing a demographic shift.

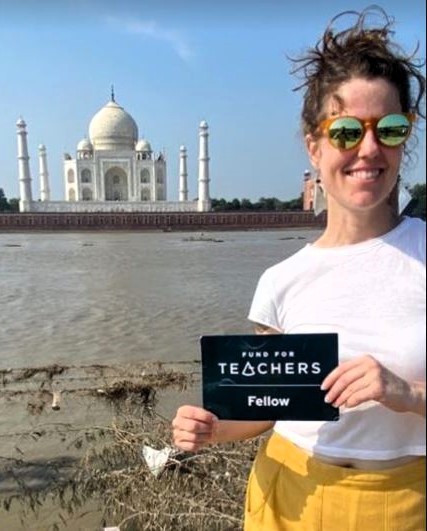

With a $10,000 Fund for Teachers grant, the teaching duo learned the techniques of traditional block printing, eco-friendly dyeing techniques, and about the sustainable fashion industry in India to create a cross-disciplinary unity between art and design that teaches students about sustainability and creating clothing that expresses their identity.

Jillian and Piotr wanted to empower their students to model change, not fast fashion that comprises 10% of total global carbon emissions annually. In addition to learning about Indian culture in Jaipur and New Delhi, they also apprenticed with artisans to learning art of traditional block printing on fabric, ecofriendly dyeing techniques, and the country’s emerging sustainable clothing companies.

“Getting a chance to meet the artisans & see how the village of Bagru — where more 400 families live and work to create the majority of the hand printed fabric in India — worked together was inspirational,” said Jill. “I also learned to take things slowly & be flexible. There were times that our plans had to change & instead of getting stressed, we took things in stride & maintained a positive attitude. The fellowship also re-inspired my teaching and provided me with so many unique learning experiences that I couldn’t wait to share with my students!”

- Artisans carved the FFT logo!

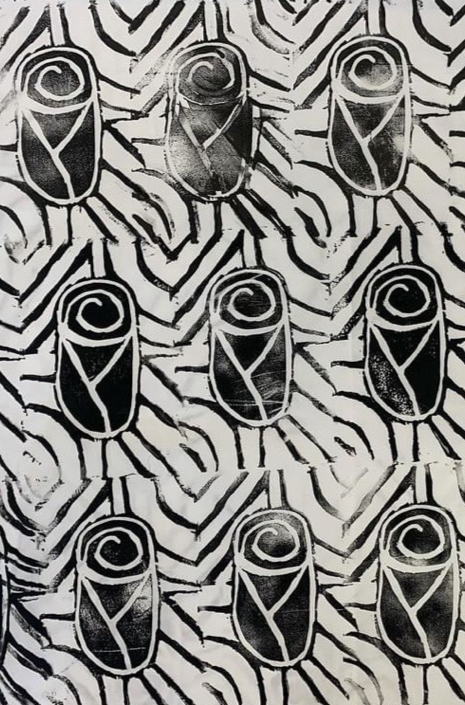

- Finished product…

Seventh graders in Jillian’s art class and Piotr’s design class wholeheartedly dove into a new hands-on unit this spring. In addition to learning about the fast fashion industry, students carved blocks with a symbol that represented their identity, used it to print their fabric, and then created a hand-sewn outfit with the fabric in their Design class.

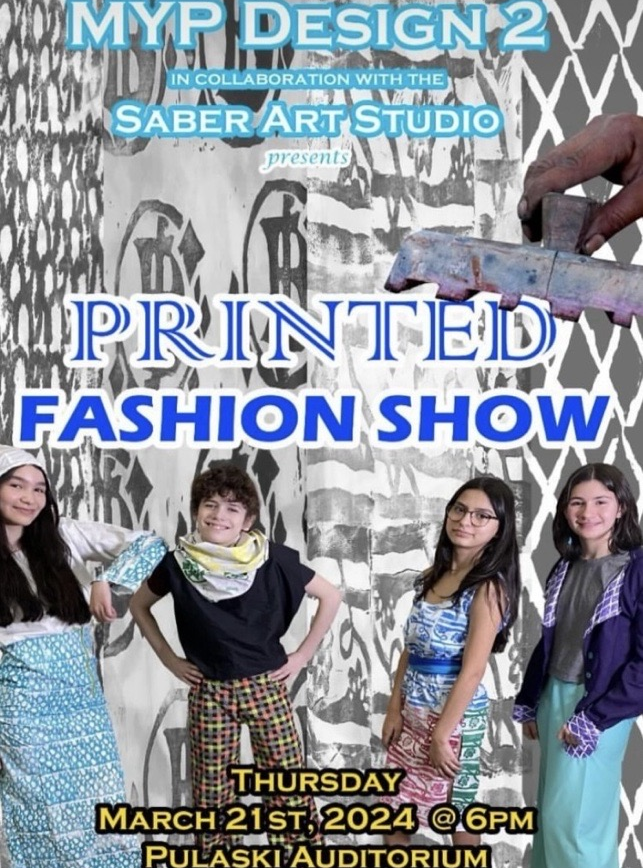

The culminating project took place in March — a community wide style show, complete with runway, lights and models of change sporting clothes they made that represent who they are. Watch their premiere here.

Richard is a middle school science teacher, sustainability coordinator, and science department chairperson in Brooklyn, New York. Currently, Richard is leading an effort that would bring recycling into his middle school. He spearheaded the construction of a greenhouse with a roof rainwater collection system. Next year, he plans to bring a reusable water bottle filtered refill station into his school. He is a

Richard is a middle school science teacher, sustainability coordinator, and science department chairperson in Brooklyn, New York. Currently, Richard is leading an effort that would bring recycling into his middle school. He spearheaded the construction of a greenhouse with a roof rainwater collection system. Next year, he plans to bring a reusable water bottle filtered refill station into his school. He is a

Julie McGowan (Albertville, AL) chose the Grand Canyon as her fellowship destination to show students the relationship between land and water. Her tour included a float down the Colorado River with a guide who incorporated her Navajo Indian heritage into the learning. Her experiences not only enhance new “Land and Water” unit that aligns with the Alabama Course of Study Science Standards, but also enriches teachers she trains as part of the

Julie McGowan (Albertville, AL) chose the Grand Canyon as her fellowship destination to show students the relationship between land and water. Her tour included a float down the Colorado River with a guide who incorporated her Navajo Indian heritage into the learning. Her experiences not only enhance new “Land and Water” unit that aligns with the Alabama Course of Study Science Standards, but also enriches teachers she trains as part of the

Students wielding knives at

Students wielding knives at  Traci worked alongside chefs at

Traci worked alongside chefs at

Beverly Brotton (Soddy Daisy Middle School – Soddy Daisy, TN) explored Alaska’s landscapes, examining how humans adapt to challenges caused by humanity and nature, to provide students a first-hand account of climate change.

Beverly Brotton (Soddy Daisy Middle School – Soddy Daisy, TN) explored Alaska’s landscapes, examining how humans adapt to challenges caused by humanity and nature, to provide students a first-hand account of climate change. Rebecca Cutkomp (East Hartford High School – East Hartford, CT) explored Washington’s Spokane Indian Reservation and Alaska’s Denali National Park to enrich student learning in thematic units on identity and aid in students’ deeper insight into rhetorical analysis.

Rebecca Cutkomp (East Hartford High School – East Hartford, CT) explored Washington’s Spokane Indian Reservation and Alaska’s Denali National Park to enrich student learning in thematic units on identity and aid in students’ deeper insight into rhetorical analysis.