We’re in the middle of Arab American History Month, but Karina Escajeda‘s impact on education is just getting started. We asked her to share how her fellowship completing Arabic language & cultural immersion in Egypt informed her career trajectory that led to her work with the Curacao Ministry of Education through the US State Department…

[minti_divider style=”1″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”][minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

My 2019 FFT fellowship to Dahab, Egypt, was built around my role as a Maine K-12 English Language Learner (ELL) Specialist. At the time, I had a professional role as an ELL Coordinator at the middle and high school in Augusta, where all of my students and their families spoke Arabic. I was also a board member of the Capitol Area New Mainers Project, a non-profit dedicated to helping New Mainers (primarily Iraqi, Syrian, and Afghani). I had been working with language learners in Maine, California and Japan, in both private and public settings, for my entire career. Additionally, as a Spanish speaker myself, I felt that the experience of learning a language and participating in a cultural immersion would be a way of connecting more personally to the central Maine Arabic-speaking community in general.

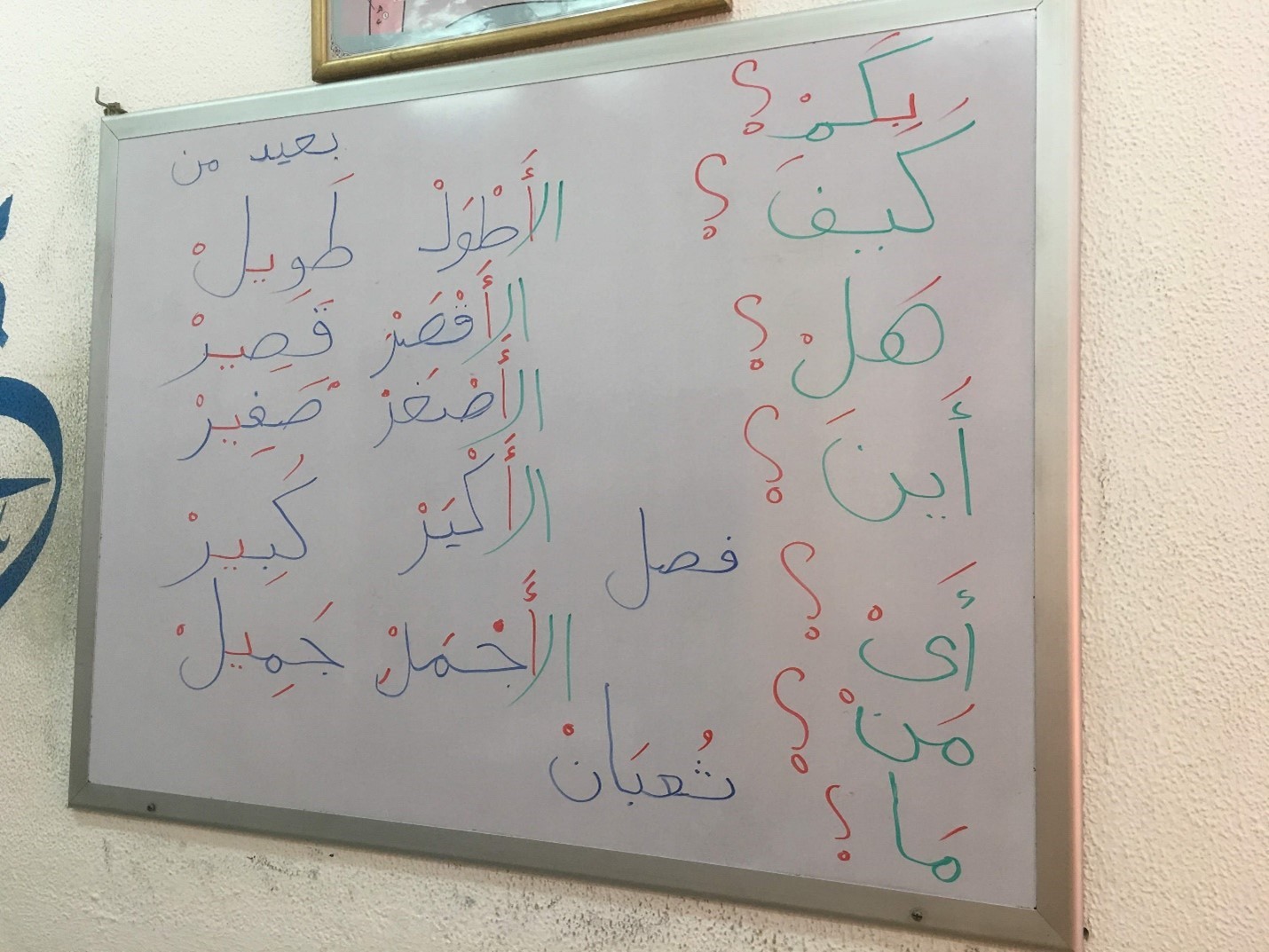

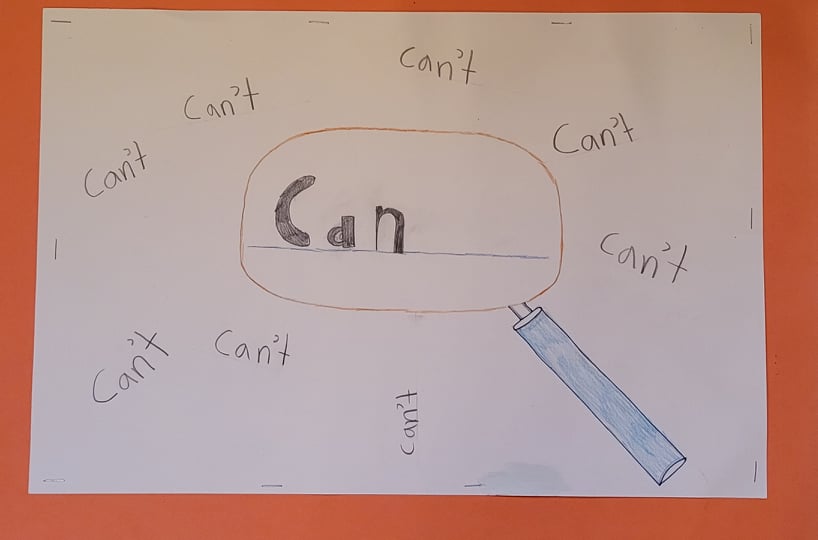

In Egypt I connected with The Futures School of Dahab and studied Arabic here for five hours a day, then practiced in the community for 2-3 more. I also had the chance to explore the pyramids along the Nile River, climb Mt. Sinai in the middle of the night to see the sun rise, and experience Bedouin culture and cuisine. While classroom drills were a big part of my Arabic instruction, my clearest memories and sharpest language retention came from interacting with people while shopping, navigating the city, and getting to know the culture and music of Egypt. The entire experience renewed my drive to make sure that all language instruction is context-based and experience driven.

During my fellowship, I was fortunate to meet up with 2019 FFT Fellow Ryan Clapp, who pursued Arabic immersion in Alexandria, Egypt, and kept an incredible blog of his experience. Although my Arabic did not become fluent in just 6 weeks (of course!), I returned to Maine with more confidence in my ability to present myself in initial introductions in the language, and the families that I work with were genuinely appreciative of the effort — and kindly encouraging about the progress that I made.

The fellowship opened my eyes, again, to my interest in creating cross-cultural connections on both a local AND global level. The meticulous effort that I put into the FFT application was transferable to my Fulbright Distinguished Award in Teaching application, which resulted in an opportunity in Greece to study effective refugee integration into learning communities and neighborhoods.

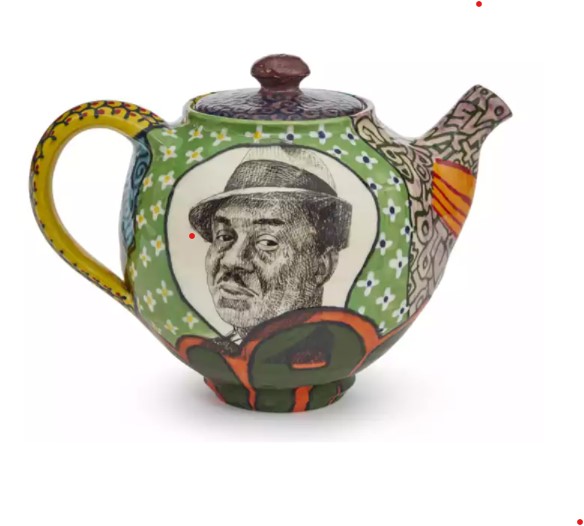

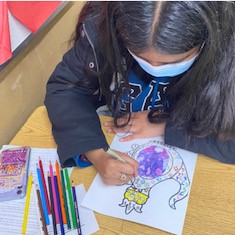

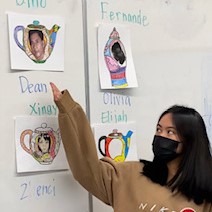

After the Fulbright project, I became the program director for Capital Area New Mainers Project, putting my teaching expertise, fellowship learning and project management skills into practice in the non-profit sphere. Once out of the classroom and working from home as the program director, it finally became possible to take on a role that I dreamed for decades: being an English Language Specialist with the US State Department. In January of 2021, I took on a contract to work with the US Consulate in Curacao, the Curacao Chamber of Commerce, and the Ministry of Education in Curacao to create the curriculum for a pilot program in the country using English (rather than Dutch or Papiamentu) as the academic language of instruction. I have developed and edited curriculum for preK through grade three, and the school is slated to open the first preK classes in August of 2023. I will remain on as a consultant for the school opening, as well as the training of teachers and administrators on the new program.

TESOL professionals who are interested in knowing more about the EL Specialist Program with the US State Department can find information here.

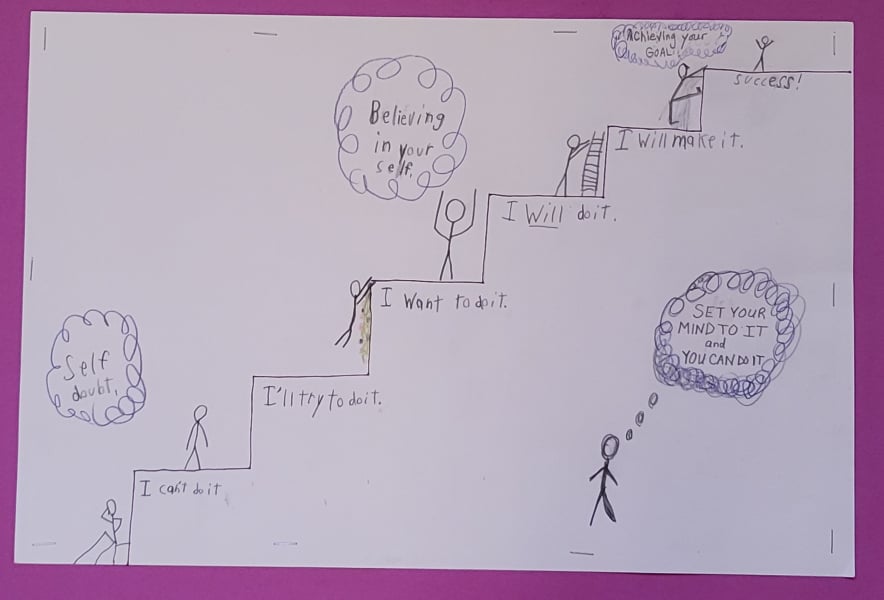

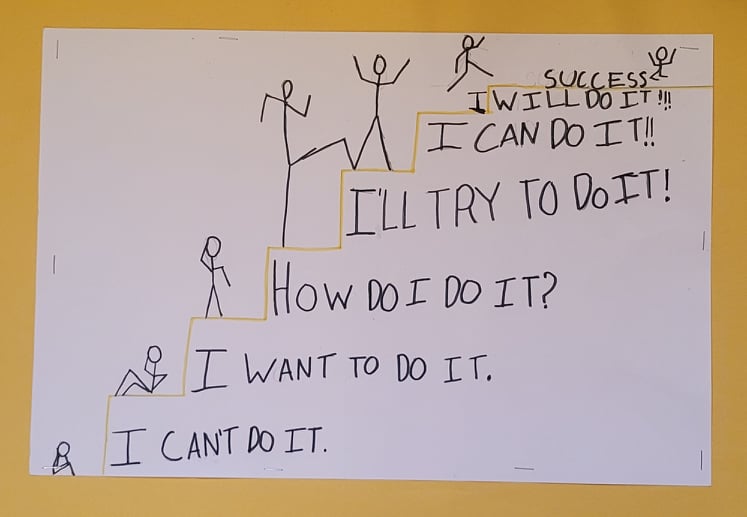

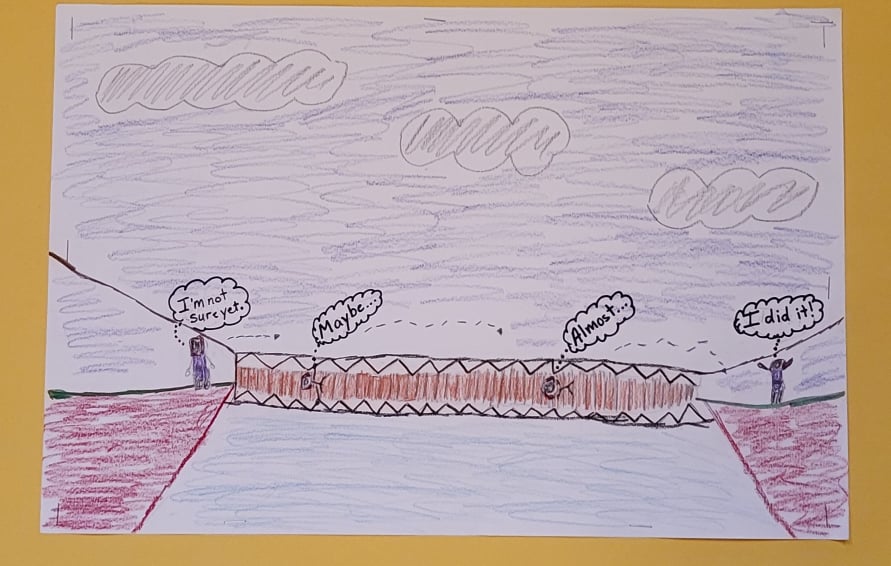

Looking back, I see that everything is connected. It is SO important for teachers to be engaged in rigorous inquiry that makes us experience frustration, but in a joyful way because it is learning that WE have chosen to do, not that has been assigned to us as part of our official duties. Students learn from people that they LOVE. That love only comes through authenticity, and teachers can’t be authentic unless we are giving parts of ourselves that are REAL — our love for learning is reignited through funding to pursue our passions.

Fund for Teachers renewed my faith that there ARE organizations in our country that see teachers as educated professionals who know themselves and their communities well enough to be effective advocates for their own needs. Equally as vital, I realized through FFT that I AM a capable expert educator who could contribute meaningfully to my hometown, region, and now — the world.

Amanda Hope is a K-5th grade Gifted/Talented Program teacher at Nancy Moseley Elementary in Dallas, Texas. Amanda has served as a classroom teacher for nearly 10 years. She most recently received the 2020-2021 Campus Teacher of the Year award at her school. In addition to teaching, Amanda is a senior policy fellow with

Amanda Hope is a K-5th grade Gifted/Talented Program teacher at Nancy Moseley Elementary in Dallas, Texas. Amanda has served as a classroom teacher for nearly 10 years. She most recently received the 2020-2021 Campus Teacher of the Year award at her school. In addition to teaching, Amanda is a senior policy fellow with

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]