Making the Grade — Differently

“Will this be on the test?”

“Can I get extra credit?”

“Are you going to grade this?”

Teachers can attest that these questions come up all the time as we introduce assignments, discuss grades, and present new material. We might get frustrated with students, feeling like they are only focused on what will be quantified, rather than on what they might learn or what skills they might develop. This has certainly been true in my own 11th Grade English classrooms over the years at a small public high school in New York City.

Unfortunately, we have only ourselves to blame.

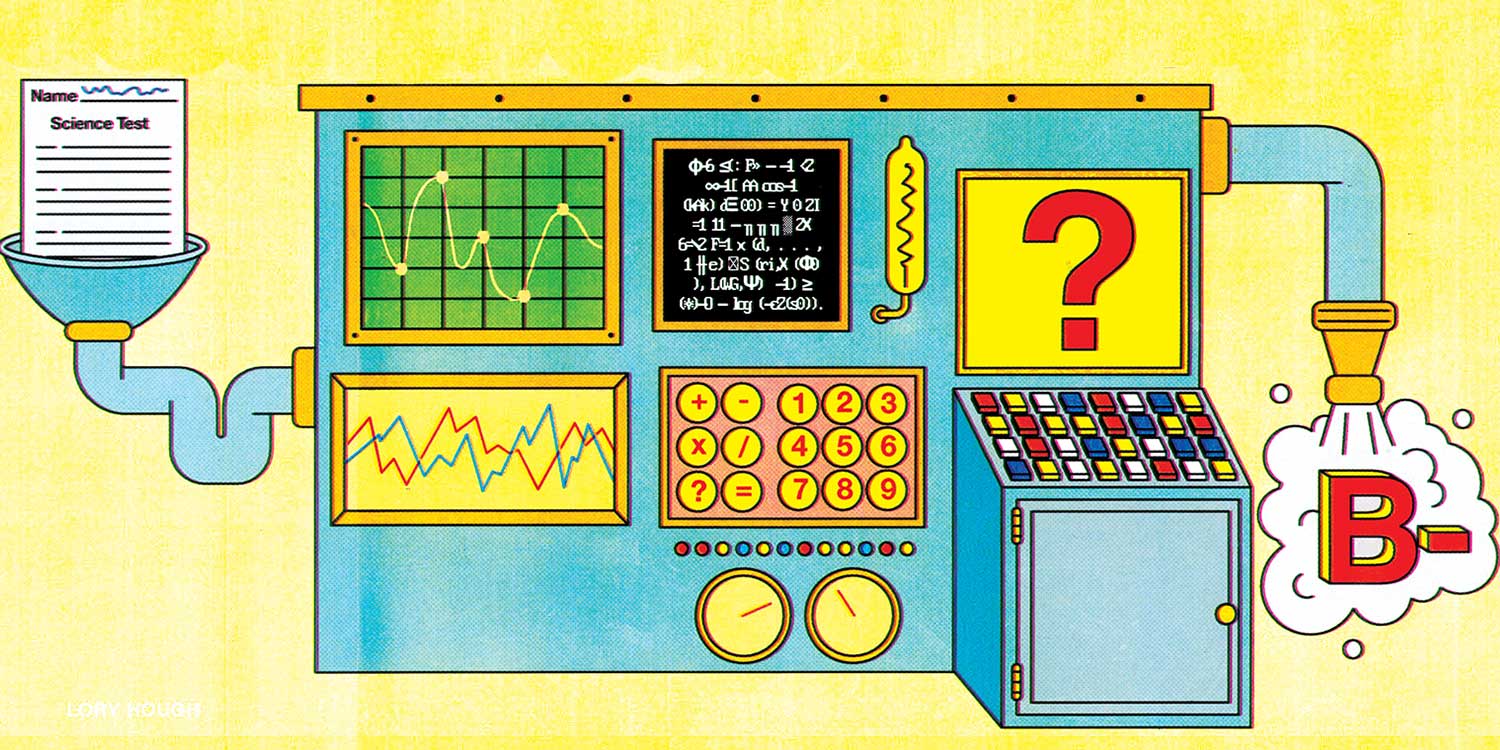

As instructors, our grading practices fundamentally reflect our goals as teachers, our values as a school community, and our overall attitudes about learning. Through our grading, we are implicitly or explicitly showing students what is important, and they adapt accordingly.

All too often, our grading routines show students that they must only do the minimum to get by, that high achievement is more important than making progress, and that making mistakes is costly and should be discouraged. Unfortunately, these routines are also counterintuitive to students making genuine improvements, taking risks, and fostering authentic learning.

When I look through my own gradebook, I can see its weaknesses as well: some assignments are connected to behavior or compliance. As such, missing assignments receive a zero. Other student work may be penalized for arriving late.

None of these grading practice decisions are connected to directly measuring student learning. Timeliness, unsubmitted work, or grades that are connected to student behavior run the risk of diverging from the measurement of actual student academic growth.

With all of these frustrations, I turn to Joe Feldman’s Grading for Equity in hopes of constructing a new system of grading that fosters intrinsic motivation, student voice, and authentic learning. And I am sold: this text inspires me to make drastic changes that I had only casually considered in the past.

The problem: I don’t know anyone who’s really done this. What could it look like? What mistakes might I make? How do I reimagine my gradebook? Will students go along with this? Are there teachers or resources that could help me work this all out?

The solution: applying for a Fund for Teachers Innovation Circle Grant that provides funding for me to buy additional texts, work with experts, and share progress with teachers pursuing similar or related work. These grants allow teachers from around the country to write proposals around some aspect of their instruction that they wish to try a new and innovative practice. Teacher projects and focus vary widely, and we collaborate at different points in the project to share progress or brainstorm around challenges.

With FFT funding in hand, I reached out to the guru himself: Joe Feldman. He is gracious and kind and connects me with a fellow High School ELA teacher (and consultant for his organization), Sara Schopfer.

In several summer sessions, Sara and I wade knee-deep into the practices and structures that might work for my classroom. She unpacks her own non-traditional grading system, unit plans, policies, and assessments. We weigh the benefits and drawbacks of various non-traditional practices.

In our FFT Innovation Circle meetings, I’m thrilled to meet Christine Paterson, a teacher in Texas undertaking similar work. We geek out about grading, and swap ideas for what these projects might look like in our individual schools. We are both the outliers at our schools trying this, so the Circle meetings offer a welcomed space to commiserate and brainstorm.

Now halfway through the year, I’ve tried non-traditional standards-based grading across my five English sections. It is a struggle to help some students adapt to a drastically different grading system; some would probably prefer to go back to our traditional grading practices.

Yet when I poll students at the halfway point in the year, I am encouraged: the majority of students want to continue with the grading experiment. They tell me they feel less stress about their grades. Several say they feel like they understand better what they are learning with the standards. Others are gratified that this grading system rewards progress more than just high achievement.

Most important to me is that students are now more actively engaged with the grading process. They make their own argument about the grade they deserve based on evidence in their work. There is more student ownership through the process.

I still have some work to do to refine the practices, but overall I am excited to disrupt and reimagine traditional systems in order to give students this voice in grading, and in their education. This, after all, is the goal: that students are not passive recipients of instruction and education systems, but that they are active agents within it.

[minti_divider style=”3″ icon=”” margin=”20px 0px 20px 0px”]

- At the Hispaniola Academy in Santo Domingo

- With Professor Mbongiseni Buthelezi at the University of Cape Town

Amy Matthusen is a four-time FFT Fellow. In addition to this Innovation Circle Grant, she has also received three Fellowship Grants: In 2007, she attended Scottish literature courses at Edinburgh University, visit and document Scotland’s literary and historic sites; in 2012, Amy enrolled in courses on South African literature at the University of Cape Town and also visit major historical sites comprising South Africa’s social, cultural and literary past, to create a unit on South Africa that promotes tolerance and challenges cultural assumptions; and in 2018, she studied Dominican history, culture, and literature through coursework at the Hispaniola Academy in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, to inform two units in two different courses intricately tied to the Dominican Republic. Amy has taught in NYC public high schools for eighteen years. She believes in bringing the outside into the classroom, and regularly invites authors and experts to video chat with her 11th and 12th grade English classes. Her career accomplishments include: Award for Classroom Excellence (now Big Apple award), Honorable Mention for National Fishman Prize, and presenting and publishing through the National Council of Teachers of English.

Back to Blogs

Back to Blogs